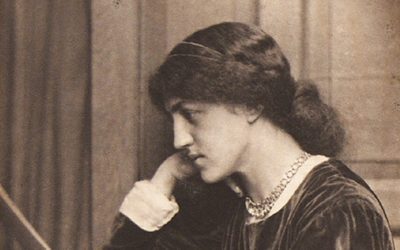

By Madeleine Joelson

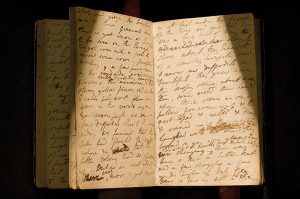

On April 15th, 1802 Dorothy Wordsworth and her brother William were walking around Glencoyne Bay, Ullswater, in the Lake District. The diary entry in which Dorothy records the afternoon is characteristic of her record-keeping. Short, informative sentences—”the lake was rough…people working. A few primroses by the roadside”—are interrupted with a description of a sea of daffodils that reaches a more poetic register:

As we went along there were more and yet more; and at last, under the boughs of the trees, we saw that there was a long belt of them along the shore, about the breadth of a country turnpike road. I never saw daffodils so beautiful. They grew among the mossy stones about and above them; some rested their heads upon these stones, as on a pillow, for weariness; and the rest tossed and reeled and danced, and seemed as if they verily laughed with the wind, that blew upon them over the lake; they looked so gay, ever glancing, ever changing.

This sea of personified daffodils, alternately weary, laughing, dancing or resting, breaks into Dorothy’s journal entry the way the daffodils themselves must have broken into the siblings’ walk. The rest of the entry returns the day to its ordinary rhythm: Dorothy runs an errand and William reads in the library before retiring.

Two years later, William would re-write this incident as one of the most famous, and possibly the most memorized, poems in the English language: “I wandered lonely as a cloud” (often referred to as “Daffodils”). We can read Dorothy’s influence over the poem in more than subject matter: for example William’s daffodils “toss their heads in sprightly dance” just as Dorothy’s “tossed and reeled and danced.” Critics began to recognize this influence as soon as Dorothy’s journals were first published nearly fifty years later in 1851. One reviewer went so far as to write that “Wordsworth’s pretty stanzas on the Daffodils are only an enfeebled paraphrase of a magical entry in her journal.”

But where Dorothy’s journal records a spectacular sight on an otherwise ordinary day, the poet transforms their shared experience into a solitary one. The poem’s climax is not really the dancing daffodils but their effect on the poet’s memory:

For oft, when on my couch I lie

In vacant or in pensive mood,

They flash upon that inward eye

Which is the bliss of solitude;

And then my heart with pleasure fills,

And dances with the daffodils.

The process of storing up restorative images as memories for later use is a common theme in Wordsworth’s poetry—reminiscent of “Tintern Abbey” and the “spots of time” episodes of the Prelude—but moments of confluence such as this one reveal Dorothy’s active role in this process. As Virginia Woolf put it in an essay on Dorothy:

Brother and sister had grown together and shared not the speech but the mood so that they hardly knew which felt, or which spoke, which saw the daffodils or the sleeping city; only Dorothy stored the mood in prose and later William came and bathed in it and made it into poetry.

Dorothy’s record-keeping has come to be recognized as an essential part of the relationship between Wordsworth’s memory and his poetry.

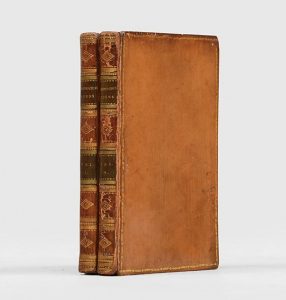

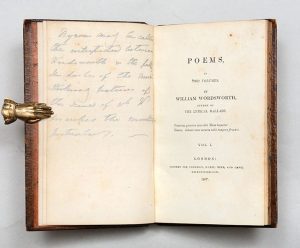

William Wordsworth’s “I wandered lonely as a cloud” first appeared in print in 1807 in Poems, Two Volumes—Wordsworth’s first publication since the 1800 edition of his and Coleridge’s groundbreaking Lyrical Ballads. The volume contains several of Wordsworth’s most famous and influential poems, including “Ode: Intimations of Mortality,” “Resolution and Independence,” “The Solitary Reaper,” and his famous cityscape sonnet, “Composed Upon Westminster Bridge.” These poems have had disparate afterlives since their original publication. The “Intimations” Ode is considered essential to understanding Wordsworth’s entire poetic project, the sonnets are celebrated as part of Romanticism’s revival of the sonnet form, and “Daffodils” has become an emblem of Lake District tourism, enthusiastically excerpted in guidebooks as well as anthologies since long before the poet’s death in 1850. In more recent years, it can be seen on magnets, calendars, in a Heineken beer advertisement, and in one rap adaptation produced by Cumbria Tourism.

Placing the poem back into its original context, however, helps to free it from two centuries of excerption and commercialization, and returns it to the context in which it was published. “Daffodils” was far from universally acclaimed upon reception. Wordsworth placed the poem in the middle of a section he called “Moods of My Own Mind”—a section which critics found baffling. They were disappointed to see the poet of Lyrical Ballads attach his “exquisite emotions” to unworthy objects in the natural world (“weeds and insects,” as one reviewer put it), calling the poems “nauseating” and “namby-pamby.” Lord Byron wrote that Wordsworth had “abandon his mind to the most commonplace ideas, at the same time clothing them in language not simple, but puerile.” But arranged together, “Daffodils” and its companion poems represented something the poet saw as “eminently poetical:” the ability of natural objects to inspire and renew a lasting sensation in the mind of their observer. Such deceptively simple observations are now recognized as one of the innovations of British Romanticism. And Wordsworth anticipated as much, writing in response to the reviews of his Poems, Two Volumes that their “destiny” was to “console the afflicted, to add sunshine to daylight …long after we (that is, all that is mortal of us) are mouldered in our graves.”

Madeleine Joelson is a PhD student at Princeton University, studying 19th century publishing.