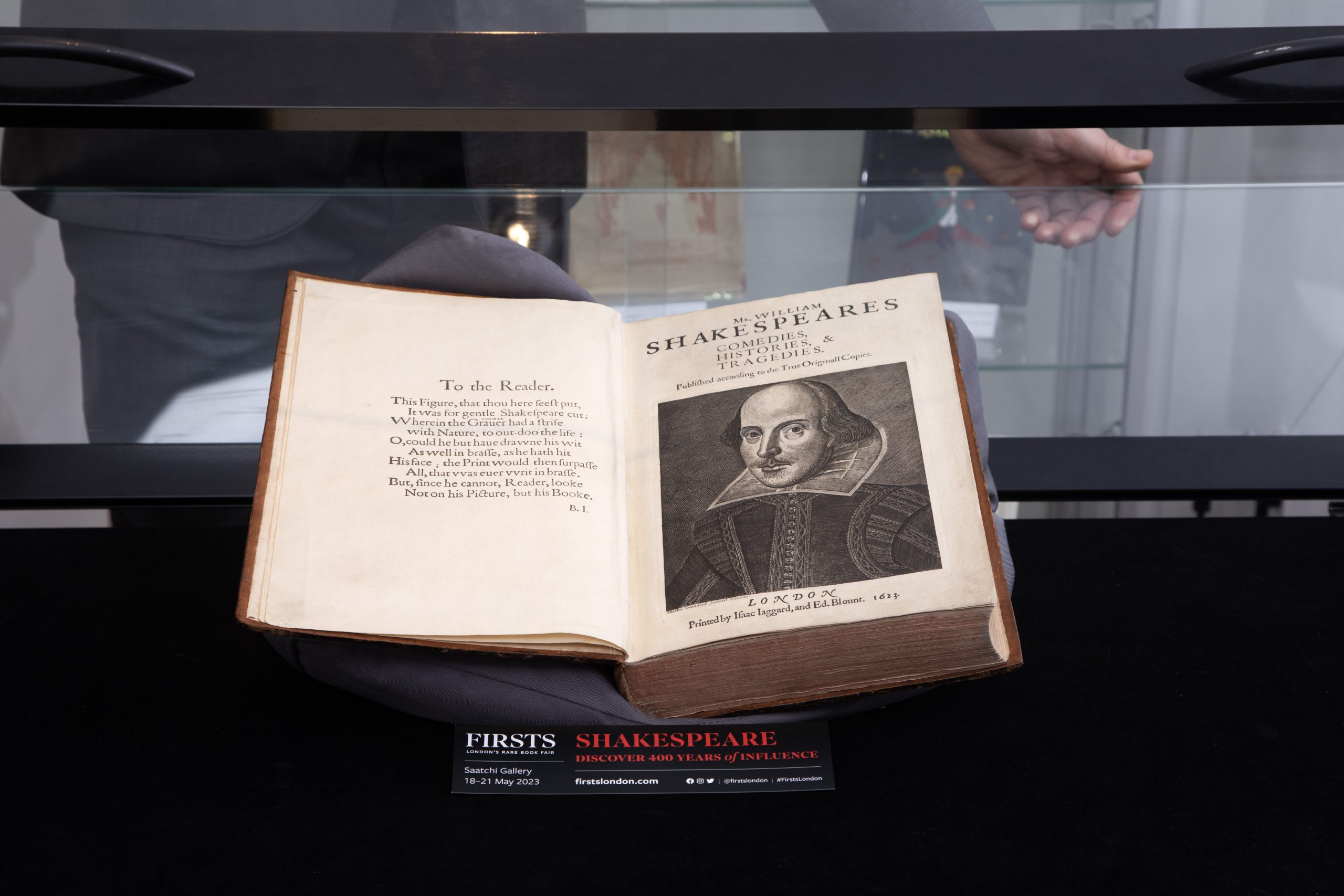

This month marks the 400th anniversary of one of the most important books ever published: Shakespeare’s First Folio. It has been credited with shaping and solidifying Shakespeare’s influence on the English language – the literal and literary heft of the First Folio granting Shakespeare’s works a prominent and permanent place in the English literary canon. However, at the time of the Folio’s publication, many of Shakespeare’s plays had started to fall out of fashion and were staged less frequently. The First Folio was the first book solely dedicated to printed plays ever to be published in the prestigious folio format – an imposing size usually reserved for religious texts such as Bibles and collections of sermons. This folio format lent a gravitas and importance to Shakespeare’s plays, marking them out as something far beyond mere entertainments, and in the process established the world’s most important literary canon.

‘The Play’s The Thing’

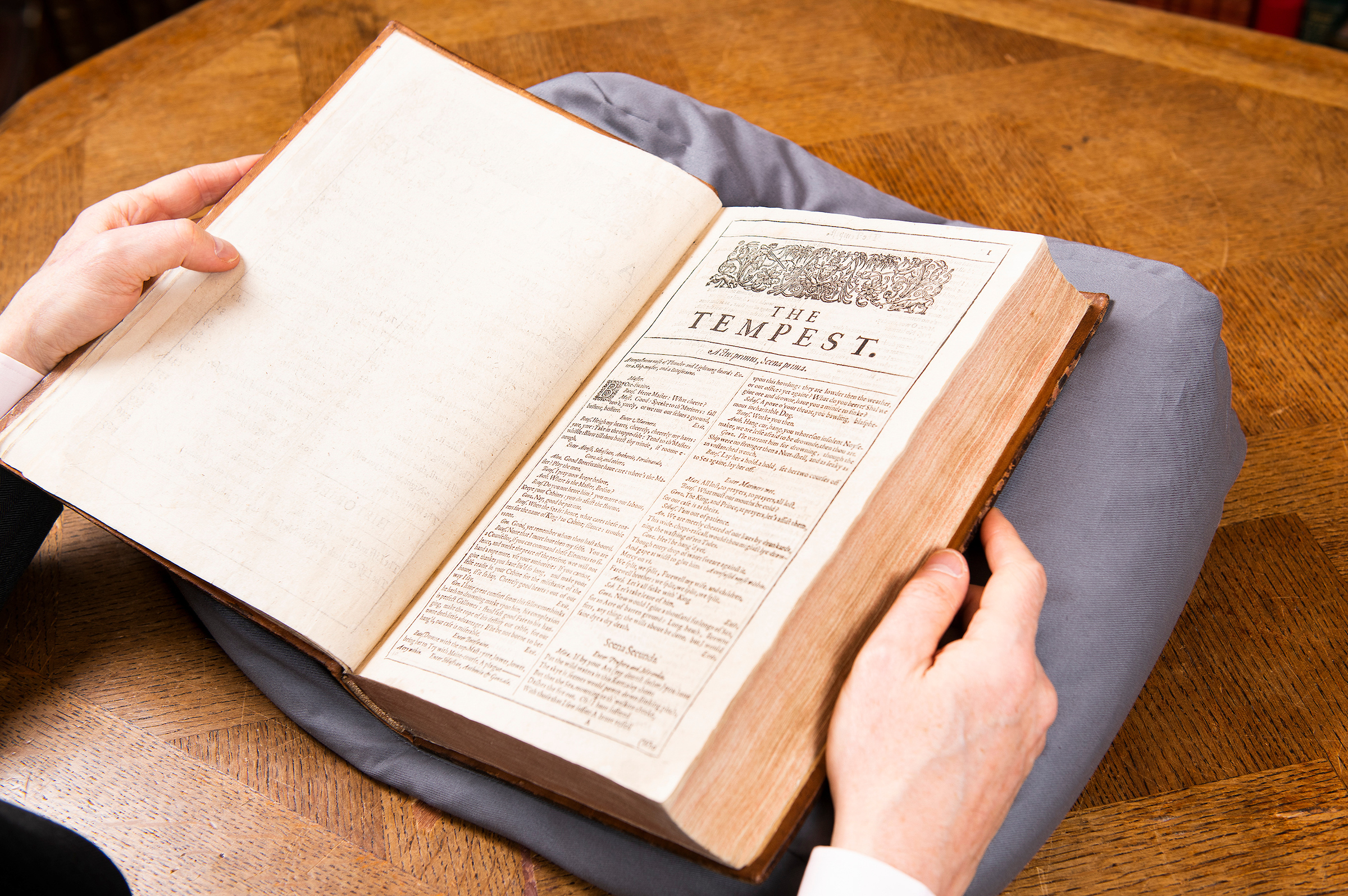

In Shakespeare’s day, plays were written to be performed, and rarely printed – and as a result many were lost. The real importance of the First Folio rests on the fact that it contains 36 plays by William Shakespeare, half of which had never been published before. Of Shakespeare’s plays, only five are missing – Pericles, Prince of Tyre, The Two Noble Kinsmen, Edward III, and the two lost plays, Cardenio and Love’s Labour’s Won. Without the First Folio, 18 of Shakespeare’s plays would have been lost forever, including some of his most loved and well-known works such as As You Like It, Twelfth Night, Macbeth, Julius Caesar and The Tempest.

The plays themselves were typeset from varying sources; many, including The Merry Wives of Windsor and Measure for Measure, were set into type from manuscripts prepared by Ralph Crane who was a professional scrivener employed by the King’s Men (the acting company in which Shakespeare belonged). Many others were taken from what are known as Shakespeare’s foul papers – working drafts of a play. When these working drafts were completed, the author or a scribe would then prepare a transcript or fair copy of the play. These copies were heavily annotated with detailed stage directions needed for a performance, and usually served as prompt books used to help guide the performance of the play.

An estimated 750 First Folios were printed in 1623; currently 233 are known to survive worldwide. More than a third of these are housed at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C., which is home to a total of 82 First Folios. On the private market they are exceedingly rare and highly sought after. One can expect a copy to fetch a price tag in the millions of pounds.

The Birth of Shakespeare’s Canon

The unpublished plays were the property of Shakespeare’s theatrical company, the King’s Men, with manuscripts in the possession of Shakespeare’s two fellow company members and friends, John Heminge and Henry Condell. They compiled the contents of the First Folio in 1623, seven years after their friend’s death, by which time most of Shakespeare’s plays had fallen out of the repertoire. Were it not for the First Folio, the scattered papers would have been worthless. With its great heft and imposing appearance, the First Folio established the Shakespearean canon for all time.

In book form, the plays found a new lease of life and sense of permanence. The First Folio was reprinted in 1632, again in 1663, and in 1685, the four Shakespeare folios spanning the century, eclipsing the rival collections of Ben Jonson and Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher, the English dramatists who collaborated in their writing during the reign of James I (1603–1625). Shakespeare was the only dramatist to achieve four folio editions in the 17th century, so the publication of the four editions in relatively quick succession set the seal of distinction on Shakespeare’s reputation as England’s foremost playwright. Shakespeare’s Elizabethan and Jacobean plays, already a little old-fashioned in 1623, were among the first to be revived in the Restoration, when the theatres reopened for business after the enforced darkness of the puritanical Commonwealth. They have continued to be performed ever since.

The Printing of the First Folio

The publishers of the First Folio were the booksellers Edward Blount and father and son, William and Isaac Jaggard all members of the Stationer’s Company. William Jaggard is sometimes seen as an odd choice by Heminge and Condell to print the First Folio because he had previously published works by other authors under Shakespeare’s name, and in 1619 had printed new editions of 10 Shakespearean quartos to which he did not have clear rights, some with false dates and title pages which are referred to as the False Folio by Shakespeare scholars.

The printing of the First Folio was probably done between February 1622 and early November 1623. It was listed in the Frankfurt Book Fair catalogue to appear between April and October 1622, however modern consensus is that this was simply intended as advance publicity for the book. The first impression had a publication date of 1623, and the first recorded buyer of the First Folio was Edward Dering, an English antiquary, who made an entry in his account book on December 5, 1623, recording his purchase of two copies for a total of £2.

Some pages of the First Folio were still being proofread and corrected as the printing of the book was in progress. As a result, individual copies of the Folio vary considerably in their typographical error with around 500 such corrections having been made in this way with the typesetters changing out and resetting the type in the middle of printing. These corrections consisted only of simple typos and clear mistakes in their own work. There is much evidence here to suggest that the typesetters rarely if ever referred back to their manuscript sources.

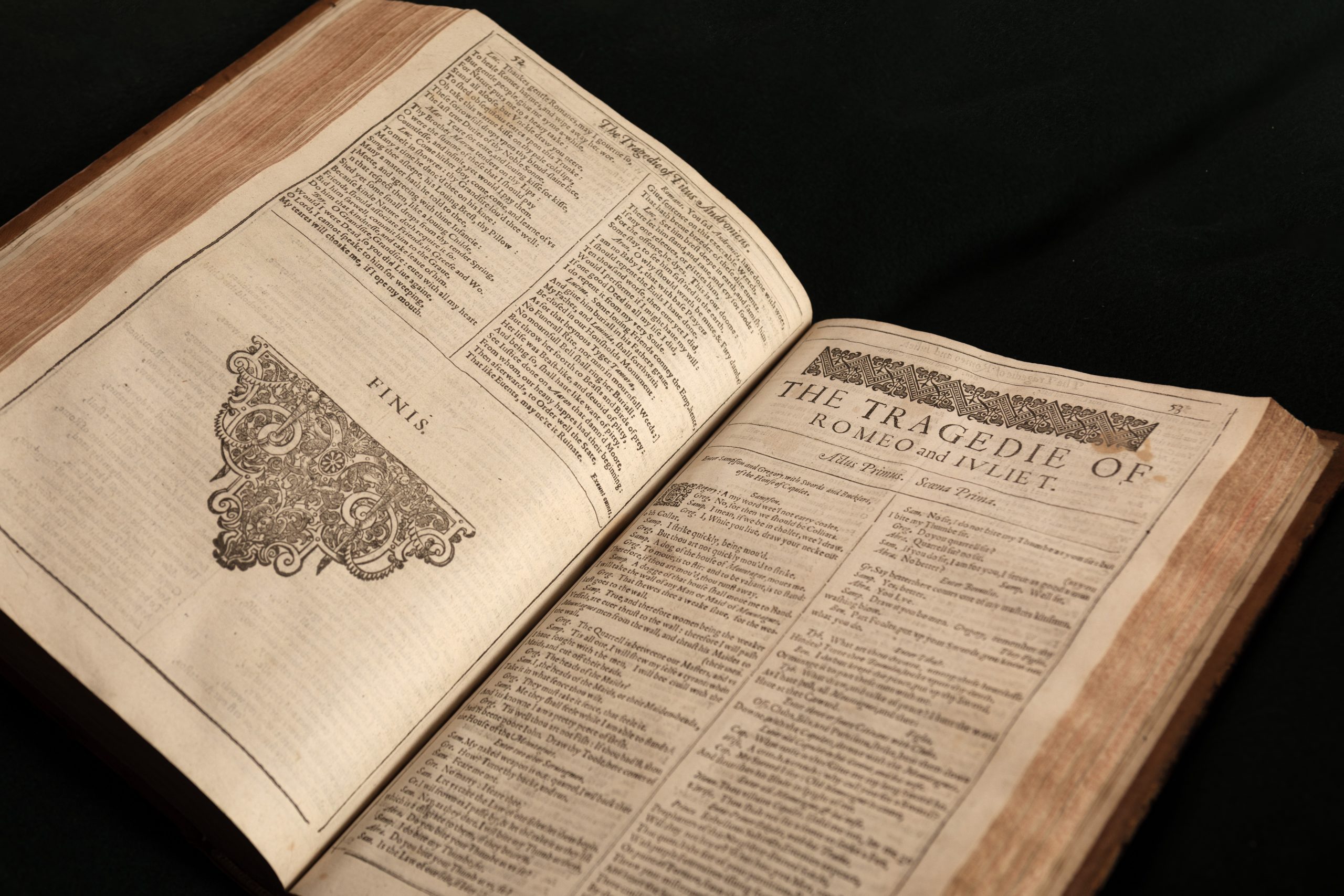

One error in the printing process was that the play Troilus and Cressida was originally intended to follow Romeo and Juliet, but the typesetting was stopped, potentially over issues with rights to the play. It was later inserted as the first of the tragedies and does not appear in the table of contents.

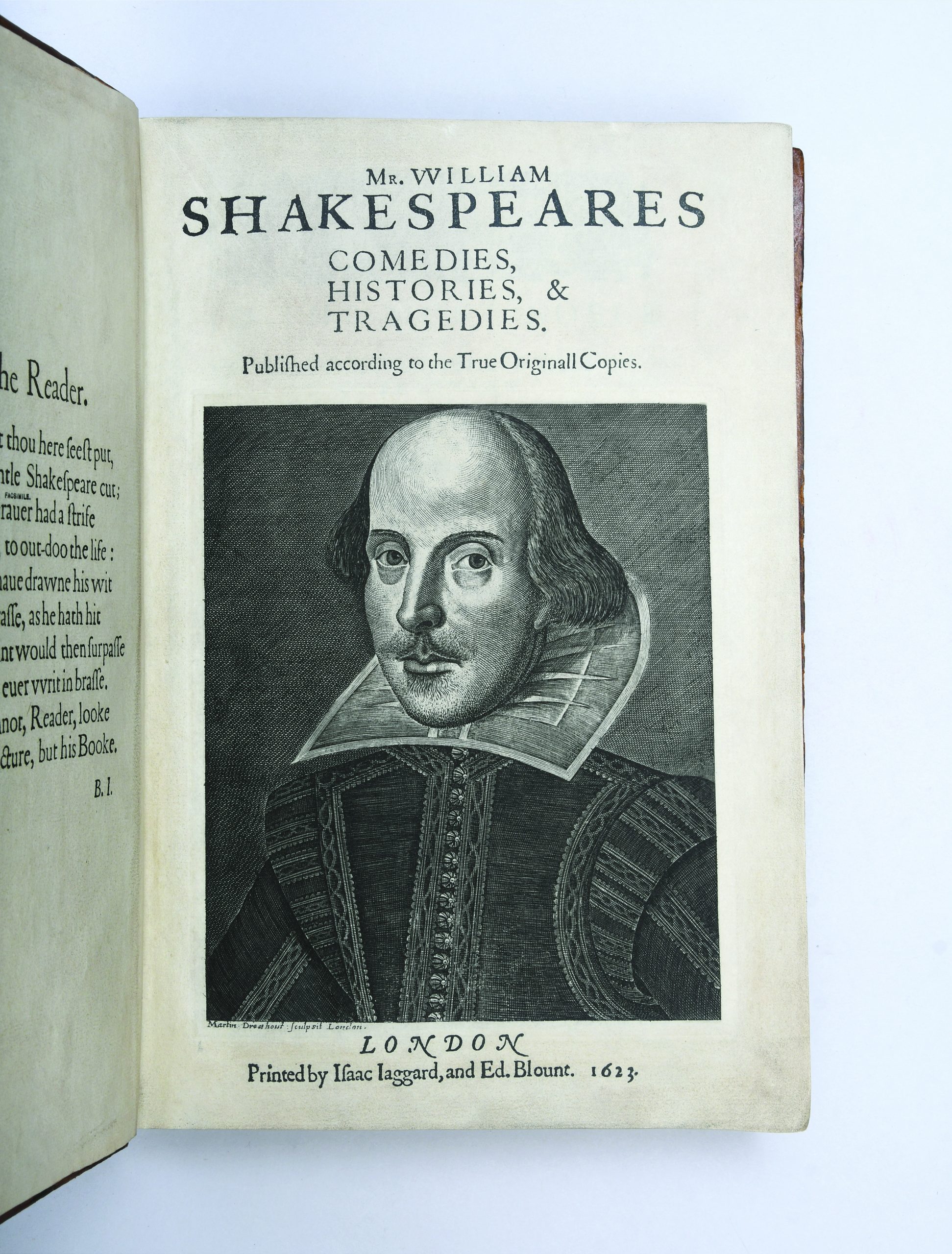

Preface to the Folio and The Droeshout Portrait

Ben Jonson, one of the most important English dramatists of the Jacobean era, wrote a preface to the folio addressed “To the Reader” is sits facing the famous engraving of Shakespeare on the opposite page. The engraving opposite Johnson’s preface is known as the Droeshout portrait and it serves as the frontispiece for the title page of the First Folio. It is one of only two works definitively known to be a depiction of Shakespeare and is thought to be based on an equally famous oil painting known as the Chandos portrait. The copperplate engraving used by Martin Droeshout to create the portrait for the First Folio was subsequently reused for all three later folios. The plate began to wear out from frequent use and had to be heavily re-engraved and re-touched with each subsequent folio.

The Book Collector’s Prize

Of the surviving copies of the First Folio most are missing some of their original leaves, with only about 56 copies complete, and many of those have been “made-up” with leaves supplied from other copies. It was during the 19th century, when the First Folio became firmly established as a popular item with book collectors, that many “improvements” to copies were made, it was common for early calf bindings to be discarded and replaced with shiny red goatskin shimmering with gilt.

The most assiduous folio hunter of all time was the president of Standard Oil, Henry Clay Folger, who bought his first First Folio in 1903 and whose Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, DC, now has the world’s largest holdings, comprising 82 copies, of which 13 are complete. The vast majority of First Folios are similarly housed in major libraries, universities, and other institutional holdings. Only 27 or so copies remain in private collectors’ hands, and only six of those are complete.

Complete copies of the First Folio emerge in commerce once in a generation. The first complete copy of the 21st century was from the library of the Chicago collector, Abel E. Berland, sold at auction by Christie’s in New York, on October 9, 2001. Known as the Canons Ashby copy and bound in early panelled calf, c.1690-1730, it had passed three times through the hands of the famous Philadelphia bookseller, Dr A. S. W. Rosenbach. Like most complete First Folios, it was not perfect and had its title-leaf and two, possibly three, other leaves supplied from another copy. It sold for $6,166,000 to Paul G. Allen, co-founder of Microsoft

Nearly 20 years later, the same auction house sold a complete First Folio that had been bequeathed to Mills College in Oakland, California, for $9,978,000. The relatively small price uplift over two decades reflects the truth that no two copies of the First Folio are strictly alike. This copy was bound in full blind-stamped russia in about 1810 and had been shown at the 1951 Festival of Britain Exhibition of Books. It had the first leaf with Ben Jonson’s verse address “To the Reader” inlaid, a few letters on the title and a portion of the portrait restored, and the last leaf re-margined. It was 15mm shorter than the copy bought by Paul Allen, having been trimmed very close at the top of the leaves, often removing the upper box-frames. These factors were enough to keep it from breaking the $10m mark. Even so, it remains the most expensive work of literature ever auctioned.

Earlier this year, in 2023, we offered a First Folio for sale at £6.25 Million which has now sold.

A Wordsmith Without Equal

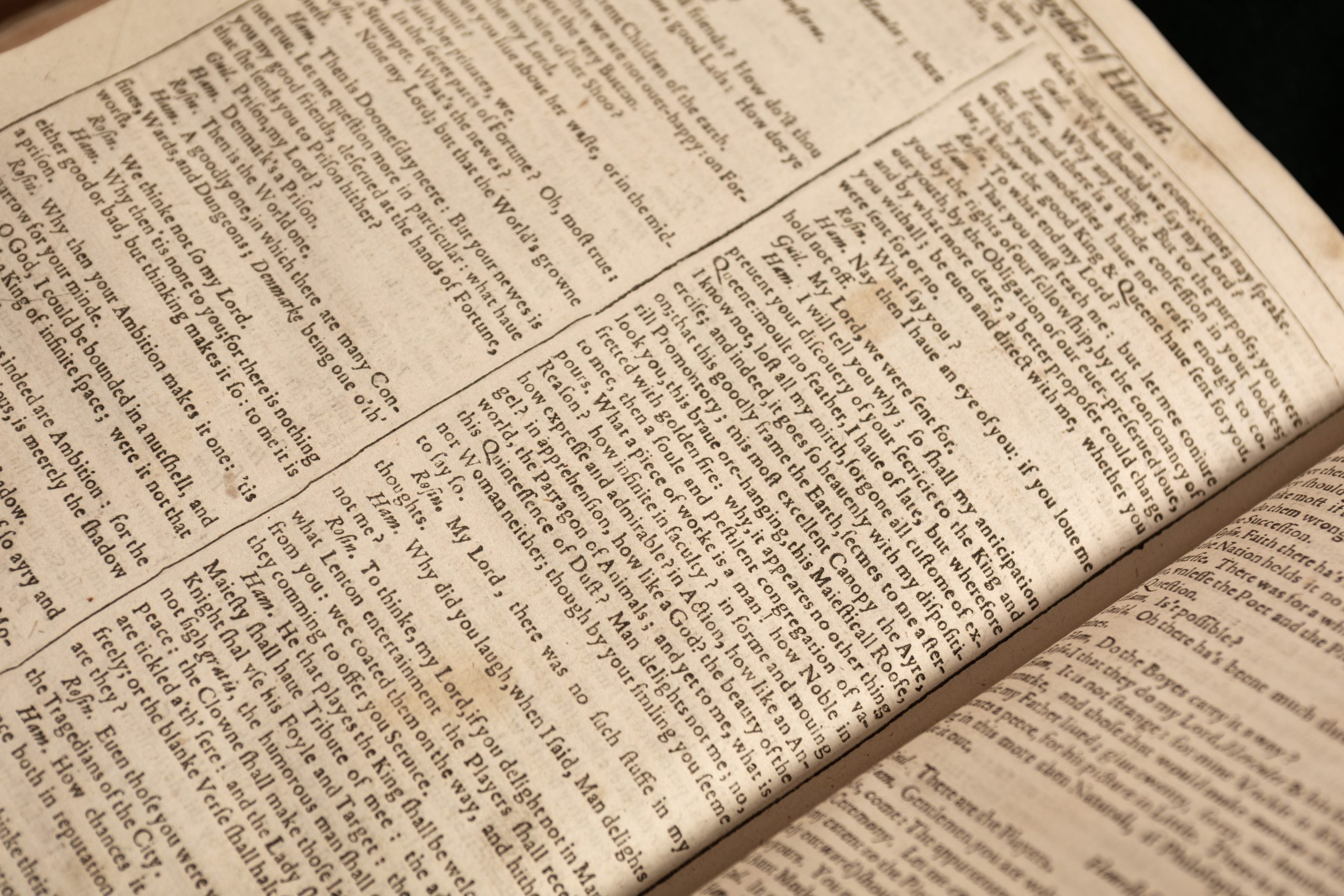

Shakespeare’s primacy as the earliest and greatest writer in modern English has led to some unsupportable claims made for him. It used to be argued that he was a preternaturally inventive wordsmith, with a huge number of original coinages attributed to him. But he wouldn’t have been so popular in his lifetime if he couldn’t make himself understood to the general playgoer. What Shakespeare displayed was an extraordinary linguistic ability to redeploy parts of speech in unexpected contexts, a process of transference known as functional shift. In Troilus and Cressida, for example, he describes how “Kingdom’d Achilles in commotion rages”, where he converts “kingdom” from a noun to an adjective. It’s the earliest instance of this usage recorded in the Oxford English Dictionary and just one of many such that we can assume to be Shakespearean creations. Shakespeare may not have plucked new words out of thin air (a phrase first found in The Tempest), but he had a special gift for combining words to create resonant phrases that made their way out of the First Folio into the English language. Only one other book, the King James Bible of 1611, has had such a profound and lasting influence on the common stock of English phrases.

William Shakespeare: Bard and Muse

It can be argued that Shakespeare’s is the shadow that all subsequent writers in the English language find themselves trying to escape from under. While Shakespeare was known for adapting existing stories and myths, it is his versions which have stood the test of time laying the foundations for subsequent re-imaginings and interpretations.

Many important modern writers, including Toni Morrison and Margaret Atwood, have created work either in response to or inspired by Shakespeare’s plays. The Bard’s ghost haunts the Scylla and Charybdis episode of James Joyce’s Ulysses, in which Joyce’s alter-ego Stephen Dedalus presents his “Hamlet theory” to a group of acquaintances in the National Library of Ireland.

The title of William Faulkner’s masterpiece, The Sound and the Fury, is taken from a line from MacBeth, as is Agatha Christie’s By the Pricking of my Thumbs, while David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest is taken from a line in Hamlet.

Even Disney has played its hand at Shakespearean adaptation most notably with The Lion King not to mention the countless film adaptations of Shakespeare’s work by famed directors such as Derek Jarman, Julie Taymor, Peter Greenaway and Kenneth Branagh.

Reinterpretations of Shakespeare’s work are not only limited to the Anglosphere with works in many other languages having been influenced by the plays collected in the First Folio; a particularly good example of this is Aime Cesaire’s Une Tempête, a post-colonial reimagining of The Tempest.

Sections of this article were previously printed in an issue of Antique Collecting.