By Madeleine Joelson

One spring morning in 1967, twenty-one-year old Humphrey Carpenter—a native resident of Oxford as well as a recent graduate of the university—made use of his local and family connections in order to pay a visit to one of Oxford’s literary giants, J.R.R. Tolkien.

Despite his growing fame and success, Tolkien was living at the time in a modest house in the “respectable but dull” suburb of Headington. The house was not, as W. H. Auden once called it, “hideous;” according to Carpenter it was “simply ordinary”. After a brief encounter with Tolkien’s wife Edith, Carpenter was led outside to a garage, which had been converted into a temporary storage space for the author’s papers and was not—Tolkien was careful to stress—the room where he wrote (although it was the room where he received visitors at this time—he was fiercely protective of his and Edith’s privacy).

Carpenter describes this visit in intimate detail as a preface to his 1977 biography of Tolkien—the book that launched Carpenter’s career as an author and, thanks to his unprecedented access to a great deal of Tolkien’s unpublished archives, became the gold standard for biographies of the author. It still is, thanks to the fact that the primary biographical sources of Tolkien’s life are still difficult to access and verify: one critic grudgingly describes Carpenter’s influence as “so pervasive as to be almost invisible”.

What Carpenter fails to mention in this brief preface is the reason for his visit: at the time, he was adapting (or planning to adapt) The Hobbit into a “play for children and adults” to be performed at the local New College School, and he was hoping to get Tolkien’s approval of the adaptation.

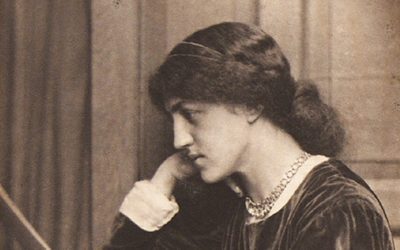

Ronald and Edith Tolkien, photographed in 1966.

Tolkien gave his permission in a letter dated 21 March 1967, but not before cutting Carpenter’s visit short in order to attend to a matter that he considered urgent:

He says that he has to clear up an apparent contradiction in a passage of The Lord of the Rings that has been pointed out in a letter from a reader…He explains it all in great detail, talking about his book not as a work of fiction but as a chronicle of actual events; he seems to see himself not as an author…but as a historian who must cast light on an obscurity in a historical document.

This addiction to precision—Tolkien described himself as “a pedant devoted to accuracy, even in what may appear to others unimportant matters”—would be enough to make any aspiring adapter nervous. But it is especially daunting when faced with a world as intricate and beloved as Tolkien’s Middle Earth.

Tolkien had his own academic reasons for mistrusting adaptation. In his 1937 lecture “On Fairy-Stories,” published in 1947, he wrote particularly on the inadequacy of visual representation when it comes to fantasy. This mistrust of the visual encompassed both the illustrative and the dramatic arts:

Drama is naturally hostile to Fantasy. Fantasy, even of the simplest kind, hardly ever succeeds in Drama, when that is presented as it should be, visibly and audibly acted. Fantastic forms are not to be counterfeited. Men dressed up as talking animals may achieve buffoonery or mimicry, but they do not achieve Fantasy.

Writing in 1938, Tolkien could not have known that his Hobbit, published the year before, would spawn decades of diverse visual representation. Perhaps nowhere is this paradox more apparent than in Peter Jackson’s transformation of The Hobbit into a lengthy and overly-epic trilogy: Jackson used innovative CGI technology and doubled the frame rate of traditional film production in order to provide, as film critic A.O. Scott writes, “an almost hallucinatory level of clarity.”

It’s hard to imagine that Tolkien would have enjoyed this kind of visual assault—one that leaves nothing to the imagination, or to the mind of the reader. But his grandson Simon, in an interview in 2012, imagined that Tolkien would have seen any film adaptation of his work as “a limiting process:” “I think he would have known what an elf would have looked like, and I don’t think it would have looked like Orlando Bloom.”

Despite this consistent distaste for adaptation, Tolkien was generous to Humphrey Carpenter in 1967. Not only did he enthusiastically give his permission to adapt the play, he also signed several books to be auctioned off each night of the performance, signed each cast member’s script, and attended the production on the final night.

We don’t know exactly whether Tolkien found the visual aspects of this particular drama to be “naturally hostile” to his fantasy world, but we do have Carpenter’s recollection of the final night’s performance. Playing double bass in the orchestra, he was able to watch Tolkien’s reactions in the front row: “He had a broad smile on his face whenever the narration and dialogue stuck to his own words, which was replaced by a frown the moment there was the slightest departure from the book.”

TOLKIEN, J. R. R.

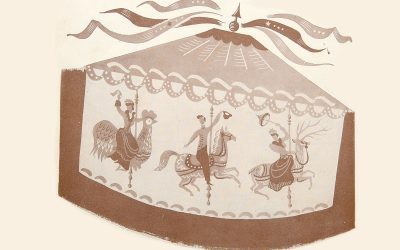

Handmade script for the New College School, Oxford, production of The Hobbit. A play for children and adults adapted by Humphrey Carpenter from the book by J. R. R. Tolkien, with music by Paul Drayton.

Oxford: New College School, 14-17 December 1967.

Notes:

A student’s illustrated copy of the script for the second theatrical adaptation of Tolkien’s The Hobbit, performed at the New College School in December 1967. This is the copy of Andrew J. A. Sharp, the First Goblin, with his lines marked in red. Together with this copy is the scarce printed programme, signed by ten of Sharp’s fellow student actors.

This production was the second such to have been performed since the book’s publication in 1937, the first being staged at St. Margaret’s School, Edinburgh, for teachers and parents in 1953. The present production was a larger affair, performed over four nights, with signed copies of the book raffled at each performance. Tolkien himself attended the final night, and Carpenter, who adapted the work, had a clear view of Tolkien’s reactions to his interpretation.

Sharp has profusely illustrated his copy of the script with endearing captions, noting that his version of the Arkenstone was “impossible to colour”. Pasted into the front is a ticket for a performance and two newspaper reviews of the show, a third of which is loosely inserted.

Description:

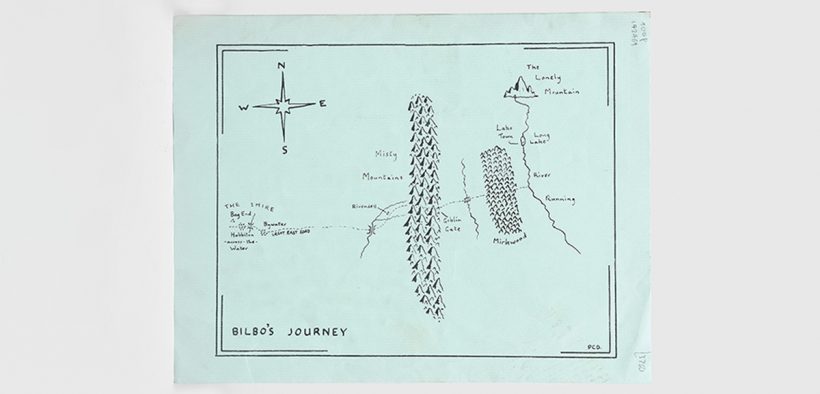

Folio (340 x 254 mm), 42 pp. typescript, printed on rectos only. Original card boards tied with treasury ties, titles and illustrations to front board in various coloured pens. Single leaf of blue thick stock paper, folded to form 4pp. (total size 279 x 430 mm). Front cover printed in black, rear cover featuring a map entitled Bilbo’s Journey printed in black. Numerous manuscript illustrations and doodles depicting scenes from the play and crude representations of fellow performers. Wear to board edges, light foxing and minor soiling to boards, small patch of early tape repair to rear board, contents and programme remarkably clean and bright, first page loose; in very good overall condition.

£3,000 (Item sold)

Madeleine Joelson is a PhD student at Princeton University, studying 19th century literature.