The South Sea Bubble, a Scene in ‘Change Alley in 1720, Edward Matthew Ward, 1847

By Hector Kociak

In modern Britain, where bold and successful inroads upon public credulity seem to be a daily occurrence, it’s natural to look for some wisdom on how to avoid financial, intellectual and moral ruin. The godly would make a sign of the cross and reach for the Good Book; Ecclesiastes 1:9 informs us in Morrissey-like fashion that “What has been will be again / what has been done will be done again / there is nothing new under the sun.” You don’t have to go back that far, however. As the Black Monday crash of 1987 wreaked devastation across world markets, many a clammy-handed trader would have felt a chill of recognition listening to the frontman of the Smiths echo their thoughts on the A-side ‘Panic’, from the aptly titled ‘The World Won’t Listen’: “I wonder to myself / could life ever be sane again?”.

If you’d travelled back a hundred and something years and asked the journalist Charles Mackay, the author of the compendium of human folly Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, the answer would probably be that life was never sane to start with, wherever you look in the historical record. From the crusades, to witchcraft, alchemy, magnetism, haunted houses and more, Mackay’s masterwork sets out in crystalline and quotable prose how men and women throughout history have been hustled, scammed, bamboozled and willingly led astray by themselves or others.

Charles Mackay

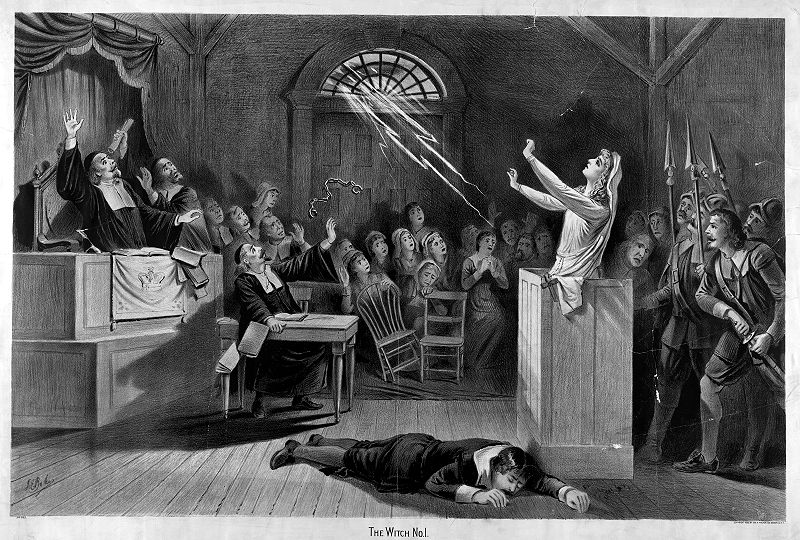

The work is an interesting combination of humour and reflection. We laugh along through the chapters on ludicrous prophecies, alchemy, “The Influence of Politics and Religion on the Hair and Beard” and “Popular Follies of Great Cities” (a riff on absurd street slang). Treatment of the Crusades and other destructive superstitions is more sober. Mackay’s exhaustive (and somewhat exhausting) treatment of European beliefs in witchcraft is suffused with clear authorial horror at a “frightful catalogue of murder and superstition”. The reader is made aware that the horrible reality really was no laughing matter.

On beliefs in hauntings and ghosts, Mackay tells explanatory stories of draughty hallways, trapped rats, and human roguery with the relish of an Arthur Conan Doyle. Amongst tales of “hams, cheeses, and loaves of bread themselves upon the floor as if the devil were in them”, particularly relatable to the modern reader is Gilles Blacre of Tour. A candidate for patron saint of all tenants, Mackay recounts how Monsieur Blacre almost managed to convince local courts in 1580 that his insufferable tenancy should be annulled on account of his home having become (in his words) “the general rendezvous of all the witches and evil spirits of France”. A worthy excuse for turning down that next unwelcome dinner party, perhaps.

Mackay does not miss the chance to draw a progressive and paternalistic lesson from these tales of folly and superstition. He highlights that the reason they appear absurd to the modern reader is because over time, modern lawmakers “by blotting from the statute-book the absurd or sanguinary enactments of their predecessors, have made one step towards teaching the people”. If ghosts and witches still remain in the popular imagination, it is the fault “not so much of the ignorant people, as of the law and the government that have neglected to enlighten them”.

The witch no. 1, J.E. Baker, c1892.

Some lessons are proving harder to learn, however. Most famously, and at the core of the book’s reputation as one of the first treatments of crowd psychology in the financial markets, Mackay recounts the absurd and entertaining details of three of history’s most notorious economic disasters, the Dutch Tulipomania, the South Sea Bubble and the Mississippi Scheme. If you’ve paid attention to any recent financial manias, the features of the delusions Mackay describes are startlingly and depressingly familiar.

The description of the Dutch Tulipomania in Chapter 3 reads almost like an instruction manual for a financial crisis. First, take a rather sub-prime asset. Make it really desirable. Let middle class vie with each other to possess as much of it as possible in the belief that prices will rise forever. Draw in the cut-throat speculators, wait until the markets hit their peak, then inject a large dose of cold sobriety. Mackay’s reportage is pithy: “It was seen that somebody must lose fearfully in the end. As this conviction spread, prices fell, and never rose again…”.

Mackay’s account has remained so influential that it was often quoted in descriptions of the recent Bitcoin bubble. In July 2010, one was worth 8 US cents. Nobody cared, until everyone cared. On 15 December 2017, a Bitcoin was worth over $19,000 and was being touted as the future of global currency. The cryptocurrency has since fallen sharply, leaving only a group of true believers and fringe speculators to tend to it. Mackay would probably point out that at least a tulip is pleasantly fragrant.

Satire of Tulip Mania, Jan Brueghel the Younger, 1640.

Mackay also repeatedly highlights how some of humanity’s greatest follies spring from a desire to solve its greatest problems. The South Sea Bubble arose from a simple and perhaps slightly too elegant scheme by the Earl of Oxford in 1711 to reduce the crushing national debt. The British government agreed to compensate (at 6% per annum) a mysterious group of merchants for taking on the debt by granting a monopoly of the South Seas trade and certain taxes to the South Sea Company. With the promise of inexhaustible riches from South America funding all of this (bearing an uncanny resemblance to the indefatigable gains of the housing market in 2000s North America), what could possibly go wrong?

Everything, frankly. By dint of its power the South Sea Company prompted stratospheric speculation in its shares and a mushrooming of fraudulent joint stock companies, plunging large numbers of the public into speculative ruin as they indulged their acquisitive instincts wherever they could. The Company itself was embroiled in a scandal of cooked books, and Mackay concludes the saga with Parliament and the Bank of England intervening shamefacedly to fix and find scapegoats for the godforsaken mess. It’s rather tempting to draw parallels with more recent financial disasters, botched investments, and political movements. Mackay’s comments are quietly scathing: “The English commenced their career of extravagance somewhat later than the French; but as soon as the delirium seized them, they were determined not to be outdone…” – a familiar sentiment for the modern reader.

The story of Extraordinary Popular Delusions as a literary object however is not one told entirely by what is between the covers, or by its popular reputation as an instructive warning from the past. Recent scholarship has pointed out that, curiously, Mackay himself was a cheerleader for a contemporary infrastructure investment bubble of the 1840s known as the Railway Mania, which saw frenzied investment in a new disruptive transport technology end with losses for many Victorian luminaries such as Charles Darwin, John Stuart Mill, and the Bronte sisters.

Extraordinary Popular Delusions does not mention the scheme except in passing – perhaps unsurprisingly, given Mackay’s aggressive promotion of railway development schemes in the Glasgow Argus at this time (even prompting a spat with William Wordsworth). The Railway Mania only merits a carefully worded footnote where it is in fact placed above the South Sea project as evidence of the “infatuation of the people for commercial gambling” – but Mackay takes it no further.

It’s quite a glaring omission. One can only guess that Mackay’s enthusiasm for free markets and the progressive powers of new transport technology led him to think, quite wrongly, that things would be different this time. Perhaps that inherent optimism explains why for its length, Extraordinary Popular Delusions reads fairly lightly even today. Neither a haughty assault on human stupidity, or an exacting work of historical scholarship, Mackay describes the work as “more of a miscellany of delusions than a history — a chapter only in the great and awful book of human folly which yet remains to be written…”. It is not a great leap to suppose Mackay knew that while he may have been a chronicler of popular delusions, it was deceptively easy to become a willing participant.

While the popular perception of Mackay’s work today is as a knowing 19th century guidebook to financial crises, its power as a starter in crowd psychology comes from Mackay’s insistence on humanising the follies he describes. No macroeconomic constructs here – just good old greed, optimism, superstition and cunning plans. Perhaps the final words should be left to the author, describing here the history of the study of the follies of magnetism with a sentiment that could well be applied to Extraordinary Popular Delusions as a whole:

“It an additional proof of the strength of the unconquerable will, and the weakness of matter as compared with it; another illustration of the words of the inspired Psalmist, that ‘we are fearfully and wonderfully made.’”

Related items:

Hector Kociak is a lawyer and writer based in London.