In his 1930 work on book collecting, Anatomy of Bibliomania, Holbrook Jackson claimed that “book love is as masculine (although not as common) as growing a beard.” Times have changed; the recent inauguration of a new book collecting prize by New York bookseller Honey & Wax, “an annual prize of $1000 to be awarded to an outstanding book collection conceived and built by a young woman”, is possibly the final nail in the coffin of the idea that bibliophilia is a man’s pursuit.

It is of course true that, historically, the best-known libraries have belonged to men. Book collecting as a hobby gained popularity in the late seventeenth century and, through the next two hundred years, was pursued as avidly as any sport by men of learning. These ‘book hunters’ were celebrated publicly for their collections, discussing and trading books in clubs, coffee houses and academic spaces – forums from which women were mostly excluded.

It is only in the last century or so that women, broadly speaking, have gained access to the financial, social and academic freedom required to become collectors in their own right, and even more recently that their passions and efforts as collectors have been given credence in the male dominated narrative of bibliophilia. Yet, it would be misleading to believe that female collectors were an entirely unheard-of phenomenon in the past. Despite the odds being stacked against them, numerous women have risen to pre-eminent positions in the history of book collecting, though their names or pursuits may not be readily remembered.

Frances Mary Richardson Currer, John James Masquerier , via Wikimedia Commons

From Fatima al-Fehri, who founded what is now the world’s oldest functioning library in 859 CE, to Queen Elizabeth I, whose passion for books saw her lavishly hand-embroider several of her own collection, historical role models for women collectors are present, if not abundant. But perhaps one of the earliest British bibliophiles whose collection received some of its due recognition in her day was Frances Mary Richardson Currer.

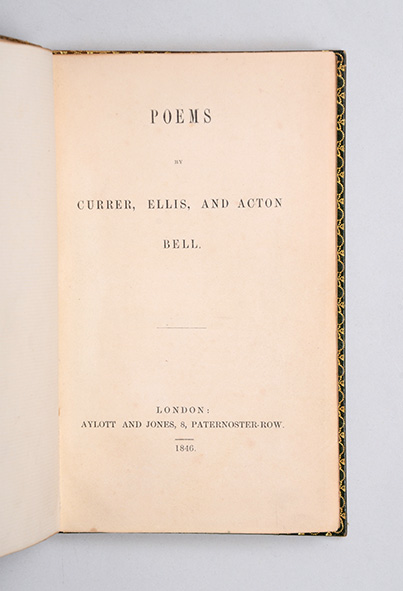

Declared by the Times in 1906 to be “the greatest woman book collector” no less, Currer had inherited a substantial library, but its expansion and curation was clearly a labour of love throughout her life. She lived at Eshton Hall in Yorkshire, not far from the Brontës at Haworth, and was known in the area as a social philanthropist. She was the generous patroness of the local school attended by the Brontë sisters and there is evidence to suggest she aided the family through a time of financial hardship. It is likely that Charlotte Brontë’s pen name, Currer Bell, under which she first published her poems and novels, acknowledges this debt of gratitude.

BRONTË, Charlotte. Jane Eyre: An Autobiography. By Currer Bell. London Smith, Elder & Co., 1848 – (BOOK SOLD)

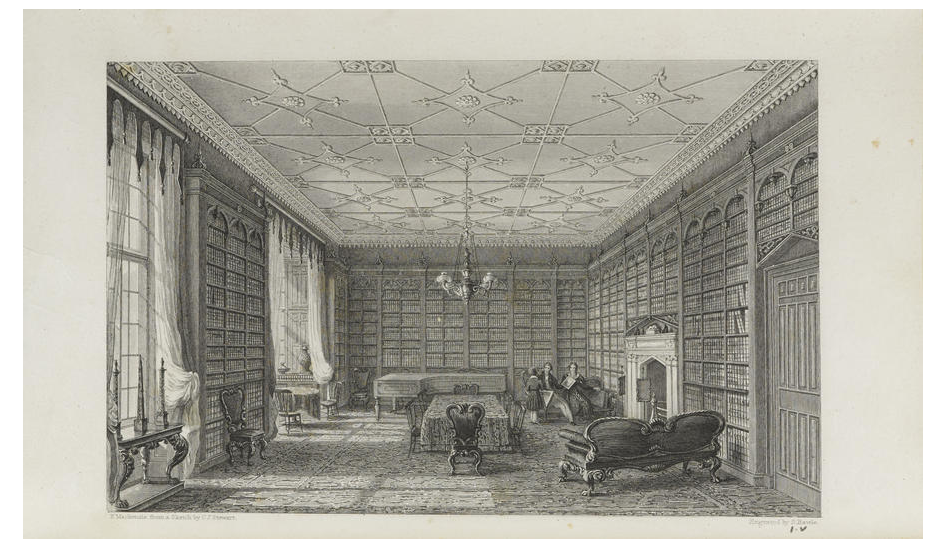

Currer’s library was, according to W. Roberts in his 1895 book on collectors The Book Hunter in London, “especially strong in British history” and was “also rich in natural science, topography, and antiquities.” She added to it extensively over her lifetime, and was a prolific reader of new titles. Her collection was deemed by eminent bibliophile Thomas Frognall Dibdin to be one of the finest domestic libraries in Europe, surpassed only in England by less than a handful of old established collections. Currer was in contact with many famed bibliophiles of the period: Thomas Phillips, who amassed a collection of manuscripts which numbered over 60,000; Richard Heber, one of the founders of the Roxburghe Club, one of the first ever book clubs; and with Dibden himself. Dibden regularly produced almanacs listing notable bibliophiles of the era and detailing their collections. However, Currer is notably absent from all these, as well as from most similar lists of collectors which appeared around the time. While the elision of women’s contribution to one area of history or another is a sad but inescapable fact, it seems that Currer herself was a collaborator in her own anonymity. Dibden, with whom she enjoyed a lengthy and fond correspondence, regularly begged her to let him include her library in his almanacs. On his specific request for a portrait of her to include in a forthcoming book entitled Bibliomania, she commented ‘I don’t doubt the book will be an amusing one — and to have the Portraits of Gentlemen in it is very proper, but I don’t think it would be pleasant for me to be in the gallery — the only Lady — so very conspicuous!’ Similarly, in a letter to Dibden on the subject, she commented that ‘Moderate notoriety is by no means desirable for a woman’.

Engraving of Eshton Hall Library, produced for a catalogue of her collection that Currer had printed in 1833.

That Currer should be so aware of the cultural bias against women bibliophiles as to foresee damage to her reputation to be thus ‘outed’ is, of course, regrettable, and is indicative of an attitude which, along with wilful exclusion, sheds some light on why accounts of women as book collectors have been so rare historically. Currer was, however, by no means the first, and certainly not the last, and there are many names which deserve recognition. In the 11th century Countess Judith of Flanders collected and commissioned a great number of illuminated manuscripts which she bequeathed to Weingarten Abbey. Several well-known historic figures, including Marguerite of Navarre, Madame du Barry, Marie Antoinette, Mary Stuart and Catherine de Medici, were passionate collectors of books and manuscripts, though this fact is rarely remembered in accounts of their lives.

Perhaps one of the most significant figures in 20th century women’s book collecting is Belle da Costa Greene. Turning her passion into profession, Greene was the librarian to J. P. Morgan for 43 years and, when the private collection was incorporated by the State of New York as a library for public uses, was appointed the first director of the renowned Pierpont Morgan Library.

Belle da Costa Greene. Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

Greene was the daughter of Richard Theodore Greener, an attorney and the first black graduate of Harvard University. Her parents had an unhappy marriage and, after their separation, Belle and her siblings changed their name to distance themselves from their well-known father. In a climate of racial prejudice, Belle invented a false Portuguese ancestry for herself, concealing her African-American heritage and passing as white for most of her life. In 1906, his collection having exceeded the size of his large study, the financier John Pierpont Morgan was looking for a librarian to organise and expand his personal library. Fortuitously, Belle, who was barely twenty but had nurtured a passion for books and illuminated manuscripts from her youth, was introduced to Morgan and he engaged her as librarian. She undertook her task with zeal, aiming to make Morgan’s library “pre-eminent, especially for incunabula, manuscripts, bindings, and the classics.” With the significant resources of Morgan’s fortune at her disposal, Belle became one of the most powerful figures in the New York book world, and helped build one of the finest libraries in the world.

As the books acquired by Greene for Morgan are largely still held in trust by the Pierpont Morgan library, it would be extremely rare for one appear on the market. Currer’s library at Eshton Hall, however, was dispersed in 1919 and many of her books, bearing her heraldic bookplate, do come up for sale every so often. We are lucky to have a few currently amongst our stock.

The bookplate of Frances Mary Richardson Currer

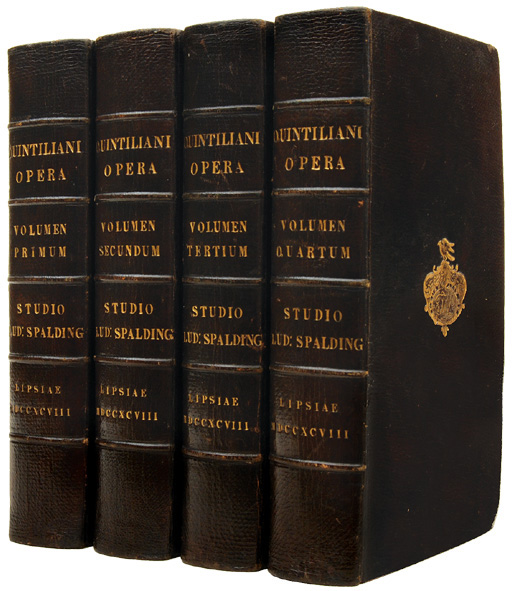

(RHETORIC.) QUINTILIANUS, M. Fabius. De Institutione Oratoria libri duodecim ad codicum veterum fidem recensuit et annotatione explanavit Georg. Ludovicus Spalding A.M. 1798.

This large paper copy of the best edition of Quintilian on rhetoric is the outstanding work of the German philologist Georg Ludwig Spalding. The binder John Clarke was “one of the best and most prolific London binders of the period” (Ramsden), who was binding from about 1820 to 1859. He joined in partnership with Francis Bedford in 1841 and they worked together until 1859, from when Bedford worked on his own. Nothing is recorded of Clarke after this date. Originally from the library of Theodore Williams and with his supralibros stamped on the cover of each book, Currer has added her bookplate to the front inside boards.

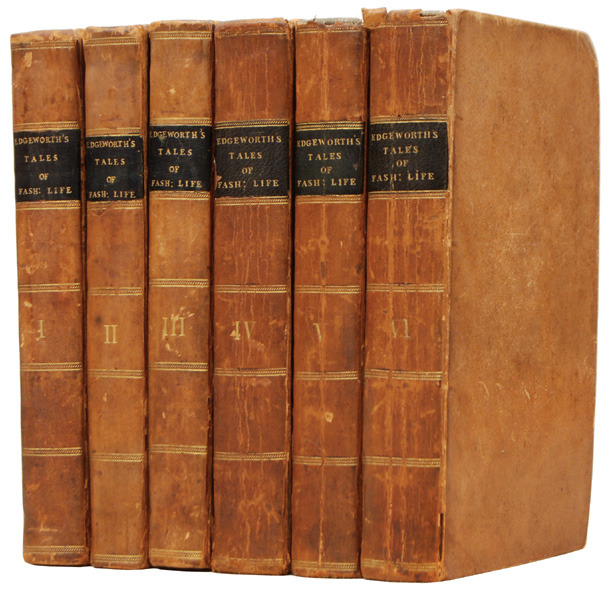

EDGEWORTH, Maria. Tales of Fashionable Life. 1809.

First edition of both series of tales, which feature stories in which a woman’s life is the predominant theme. Maria Edgeworth was the leading Irish intellectual woman and the most commercially successful novelist of her age, vying with Jane Austen in terms of contemporary critical esteem. Currer’s bookplates appear in each volume of the set.

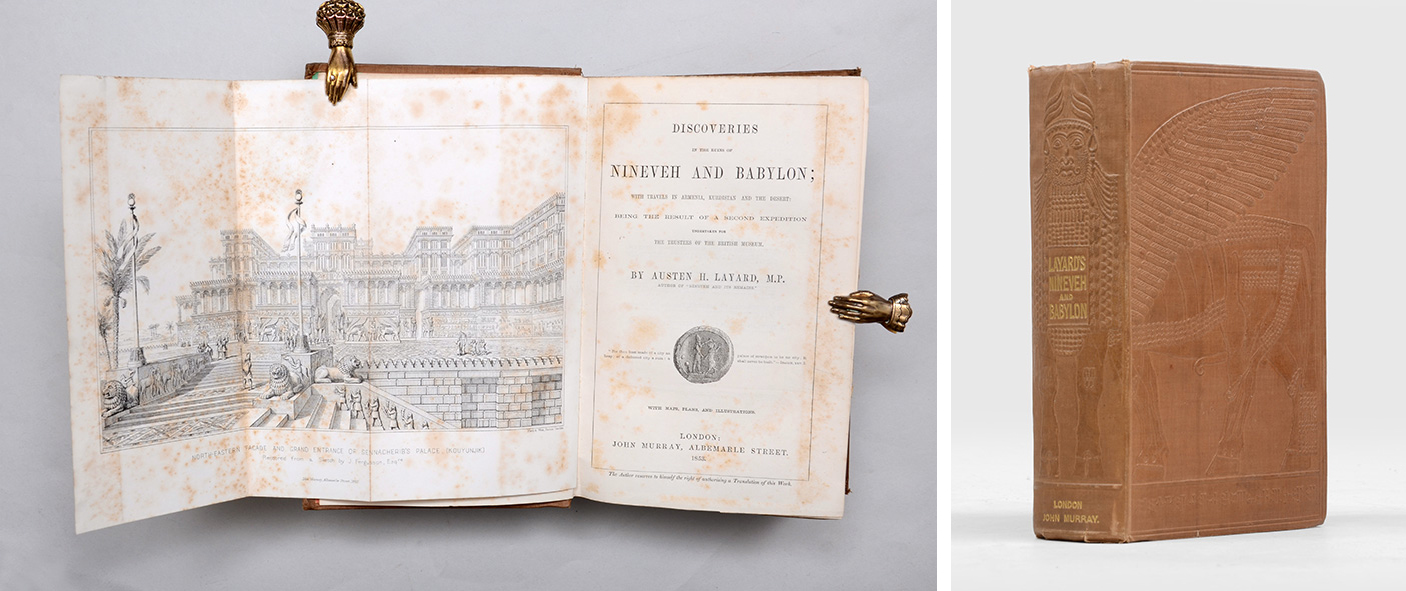

LAYARD, Austen H. Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon; 1853 – (BOOK SOLD)

Sir Austen Henry Layard was a leading nineteenth century British archaeologist specialising in ancient Mesopotamia and Assyrian civilisation. This book, part travel writing, part archaeological study, follows Layard’s second British Museum exhibition which yielded many important discoveries about Assyrian culture. The original cloth binding is particularly decorative and bears and image of the Winged Bull of Nineveh across the spine and boards.

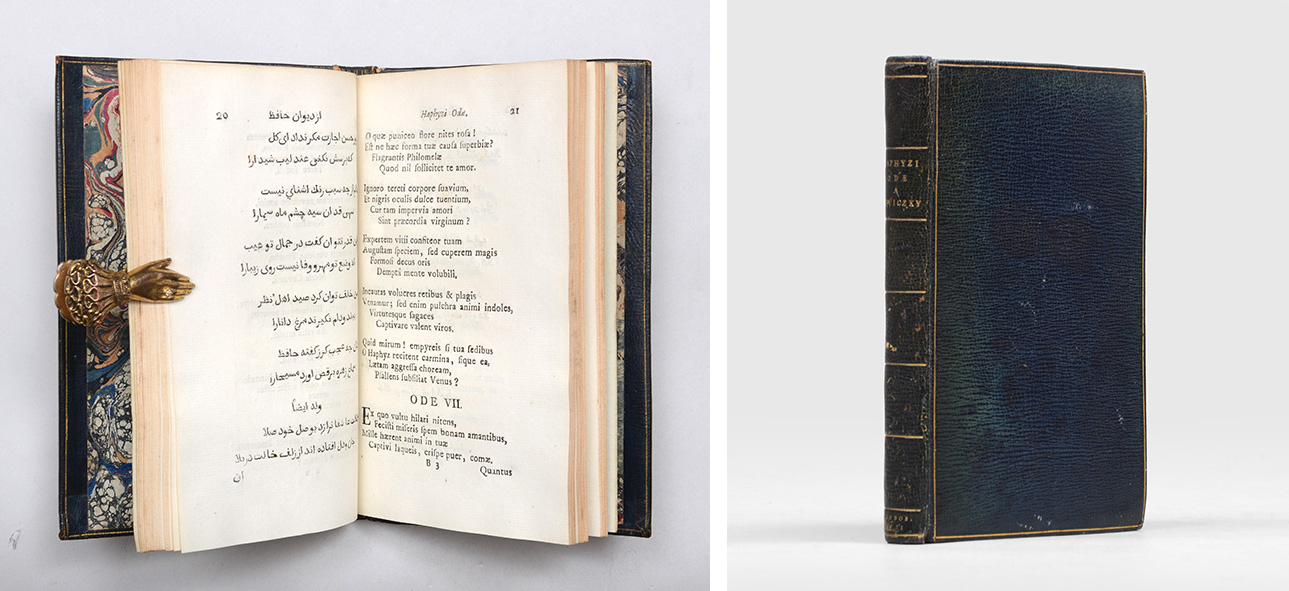

HAFIZ, Shams al-Din Muhammad. Specimen Poeseos Persicae, 1771 – (BOOK SOLD)

First edition of any substantial part of the Hafiz corpus in the original Persian, compiled by Austro-Hungarian diplomat and Persianist Count Karl Emmerich Reviczky (17371793). Hafiz is said to represent “the zenith of Persian lyric poetry” (Encyclopaedia Iranica). this volume bears both Currer’s bookplate and that of her maternal grandfather Matthew Wilson, indicating that it is one she inherited with the rest of the library.

Thanks to Lucy Saint-Smith for her help on tracing the quotes from Currer’s letters used in this piece.

If you would like to make an enquiry about selling a book, please fill out the form which can be found here.