Painting by Words: The Original Drawings of Charlotte Brontë

In 1848 the publishing firm Smith, Elder & Co. wrote to Charlotte Brontë to request that she personally illustrate the second edition of Jane Eyre. The author’s modest response will be familiar to anyone who has in later life revisited the artistic output of their childhood and teenage years,

“I have, in my day, wasted a certain quantity of Bristol board and drawing-paper, crayons and cakes of colour, but when I examine the contents of my portfolio now, it seems as if during the years it has been lying closed some fairy has changed what I once thought sterling coin into dry leaves, and I feel much inclined to consign the whole collection of drawings to the fire” (Alexander and Sellars p. 36).

Luckily, this did not happen. Today 180 original drawings can be attributed to Charlotte, and we have had the privilege obtain two of these for a client. What can they tell us about her life and the inspiration for her novels?

Charlotte, Emily, and Anne Brontë were introduced to art in the same way as thousands of other middle-class Victorian women, through the copying of prints. These had been a popular art form since the late Middle Ages, but it was not until the early nineteenth-century that technological innovations made them available on a truly wide scale. Even the poorer members of society might have one or two decorating their homes, and gift books full of romantic portraits, dramatic landscapes, and Biblical and literary scenes proliferated. This interest in the picturesque dovetailed with a new emphasis on providing middle-class women with “accomplishments”, so that drawing joined embroidery and music as a requirement for girls of the aspiring classes. Women were not expected to become creative artists, but to produce artwork as a constructive use of leisure time – to ornament their homes and to create gifts and portraits of family members. Because of this limited scope girls were not usually encouraged to draw from life as their brothers did, but to learn by copying the now ubiquitous commercial prints until they could reproduce them exactly.

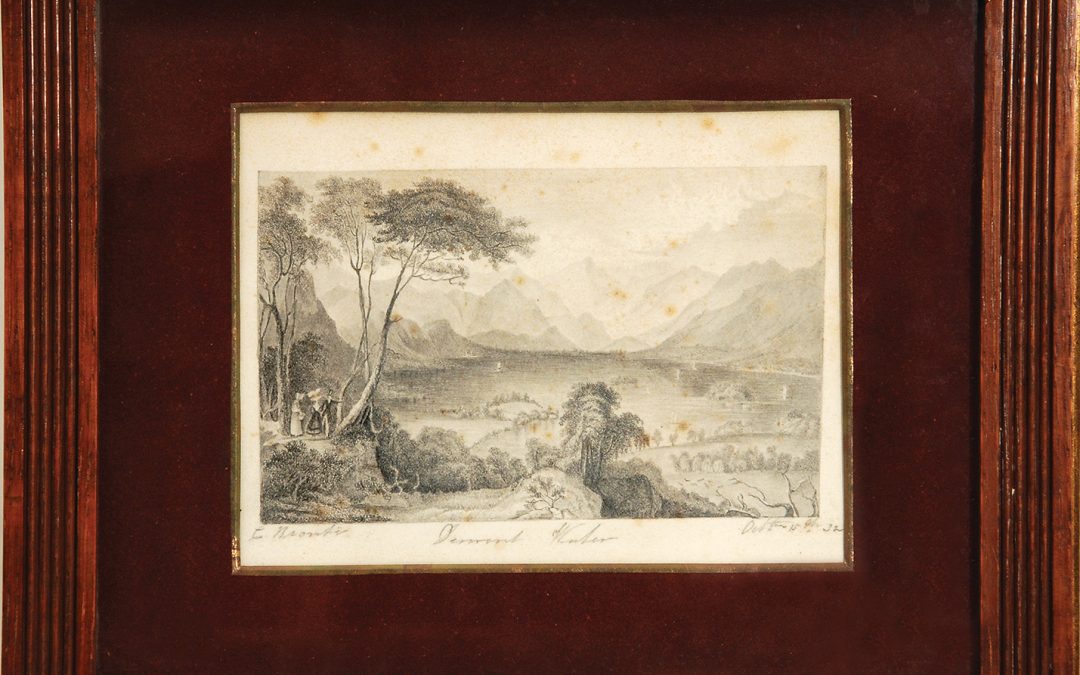

The Brontë children were eager artists and authors from a young age, and the girls received exactly this type of training, both at home and at boarding school. A good example is below, an original pencil drawing by Charlotte Brontë from Thomas Allom’s engraving of Derwent Water in the Lake District. Allom published a number of volumes of landscape engravings during the 1830s, and Charlotte is known to have made other drawings based on his work. This one has long been known to Brontë scholars but was unaccounted for during the twentieth century, and was only verified as depicting Derwent Water when it resurfaced at auction this year (click to enlarge).

Original pencil drawing by Charlotte Brontë of Derwent Water in the Lake District, dated 1832 and based on an engraving by Thomas Allom.

Charlotte was ambitious, “as a girl of twelve she was keen to cultivate a discerning mind and refine her taste in art: ‘She picked up every scrap of information concerning painting, sculpture, poetry, music, etc., as if it were gold’ (Wise and Symington, 1.92)” (ODNB). She also chafed against the restrictions imposed upon her, living with “a constant sense of unfulfilled desire and ambition” (ODNB). For Charlotte art was not just an “accomplishment”, but a potential career and a way to avoid the only futures available to unmarried women of her standing–teacher or governess. Hoping to work as a professional miniature painter, she diligently copied prints until she became an accomplished amateur, even exhibiting two drawings at Leeds in 1834. But she rarely drew from life or from her own imagination, and gradually realised that she would never overcome the restrictions of this form of artistic education. Instead, she focused on writing, and she and her sisters published their first book, Poems, in 1846 under the male pen names of Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell. In the following year Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights and Agnes Grey all appeared.

It may seem that the Brontës’ careful copies of prints by other artists have little to do with their genius as authors, but this is far from the case. As Christine Alexander and Jane Sellars point out in The Art of the Brontës, “The visual image sustained and nurtured the early lives of the Brontës”, enabling them to “visualise other worlds… to transpose the subjects and languages of pictures into their literary work. For all the Brontës, a knowledge of the visual arts, the habit of reading pictures, and the practice of drawing and painting, were crucial to their development as writers” (Alexander & Sellars p. 9).

During the nineteenth century, prints were the primary way that most people accessed images of fine art, contemporary events, and important places, and the young Brontës were no exception. Much of the visual and verbal imagery in their juvenalia was sourced directly from literary prints or illustrated books, particularly those of authors such as Scott, Burns, Shakespeare, and Milton. Natural history engravings and rural scenes by Thomas Bewick, and the dramatic Old Testament panoramas of John Martin, contributed to the siblings’ fertile imaginations, and Byron was a profound influence on all four children. During the early 1830s Charlotte copied portraits of Byron himself, as well as sublime landscapes and Byronic heroines who directly influenced the characters in her own fiction. Below, a drawing by Brontë of an unidentified woman whom scholars originally identified as Anne Brontë, but which was most likely copied from an engraving.

Pencil drawing by Charlotte Brontë of an unnamed woman, probably copied from an engraving. This piece was previously identified as Anne Brontë and was used as the frontispiece for The Tenant of Wildfell Hall in the Thornton edition of the sisters’ collected works published in 1907, but this identification is questionable.

Brontë’s focus on prints also affected her writing is less obvious ways, in her “close observation of detail in character and scene, her sensitivity to colour revealed in description and imagery, her fondness for the vignette, her method of analysing a scene as if it were a painting, and her tendency to structure a novel as if it were a portfolio of paintings” (Alexander & Sellars p. 56). A contemporary critic praised Jane Eyre because, “The pictures stand out before you: they are pictures, and not mere bits of ‘fine writing’. The writer is evidently painting by words a picture that she has in her mind, not ‘making up’ from vague remembrances, and with the consecrated phrases of ‘poetical prose'” (Alexander & Sellars p. 56).

Most tellingly, Brontë incorporated her own experiences into her novels. The heroine of Villette criticises her own “curiously finical Chinese fac-similes of steel or mezzotint plates”, and Jane Eyre begins her education by copying prints, but realises the naiveté of her early efforts and eventually becomes what Charlotte was unable to be – a creative artist working from life rather than static engravings.

For more information on this topic the best guide is The Art of the Brontës by Christine Alexander and Jane Sellars (Cambridge University Press, 1995).

Visit our shop website to see our full range of rare books by Charlotte, Emily, and Anne Brontë.

Recent Comments