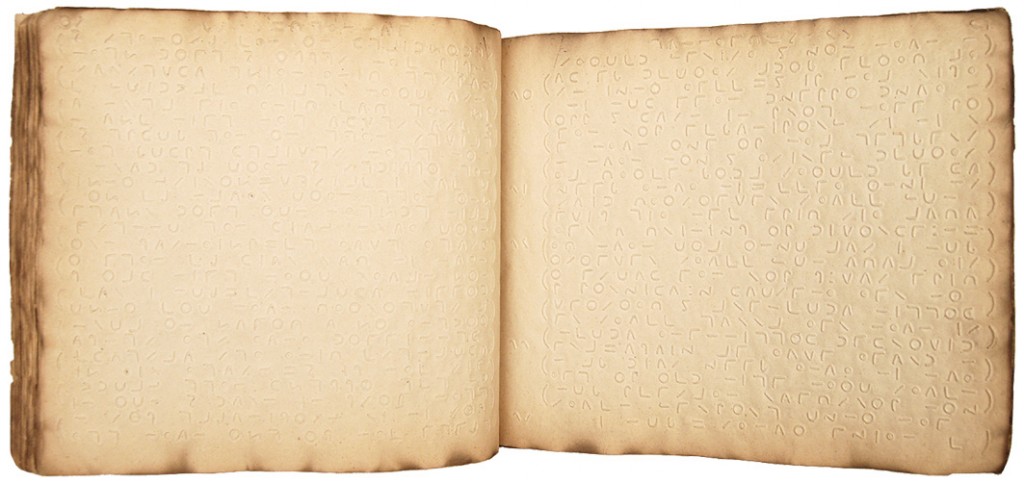

Scrapbook

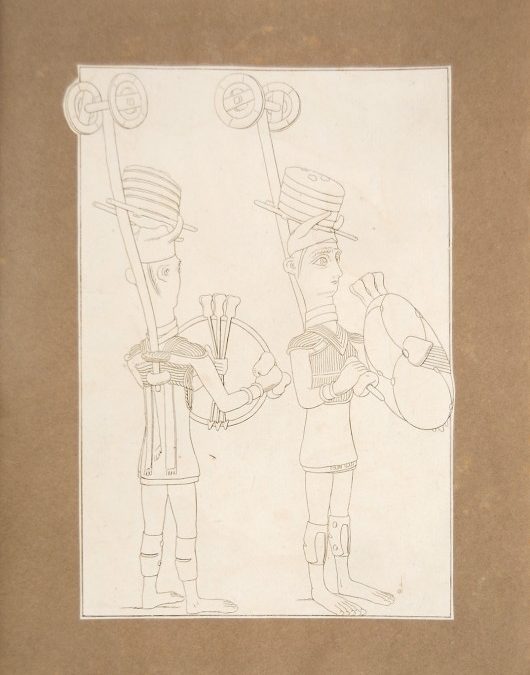

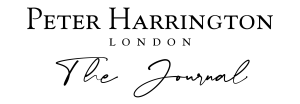

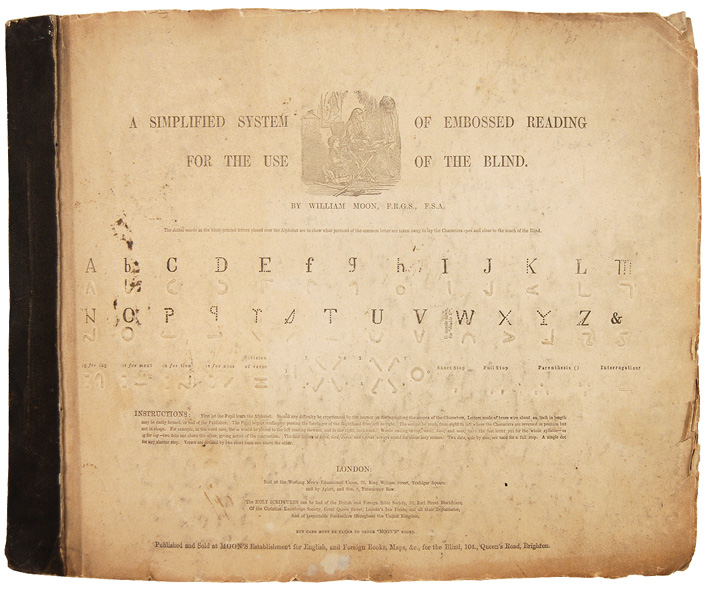

Does anyone know what this is?

All we know is that it’s the most interesting page from a 19th-century scrapbook we recently acquired. And to be honest, the mystery is probably more fun than learning the truth, as the last couple of days have been dominated by discussions of “what the wheel is for” (he runs along an electric tram track, obviously) and “why does he have a sponge cake on his head?” August is a slow month in the book trade.

Even disregarding the silly picture the scrapbook is great. The hobby was incredibly popular–as early as the late 18th century stationers were selling blank books for people to fill with prints and other ephemera, and it remained an important activity for young women throughout the nineteenth century.

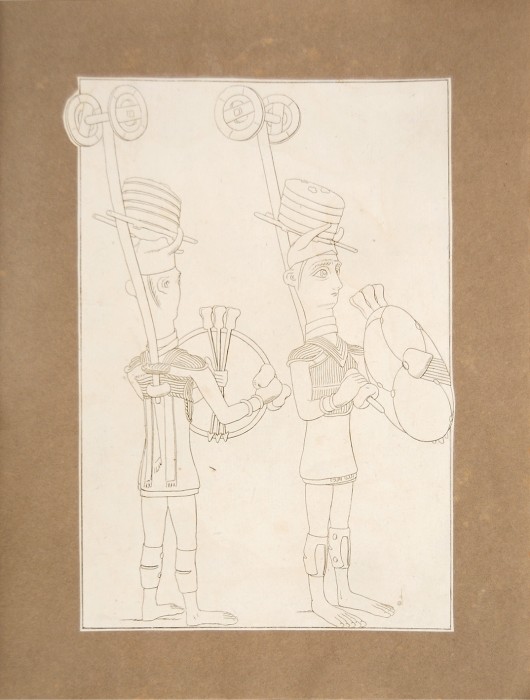

This particular book was produced in 1829 (according to the title page), and the binding is typical of the period: red half skiver, a form of cheap, thin leather produced from the inner side of a sheepskin. We can tell that this scrapbook was well cared for because the fragile skiver has not deteriorated. The book’s condition and the obvious care taken in cutting out, placing, and coloring the scraps within it indicate that it was a much-loved item.

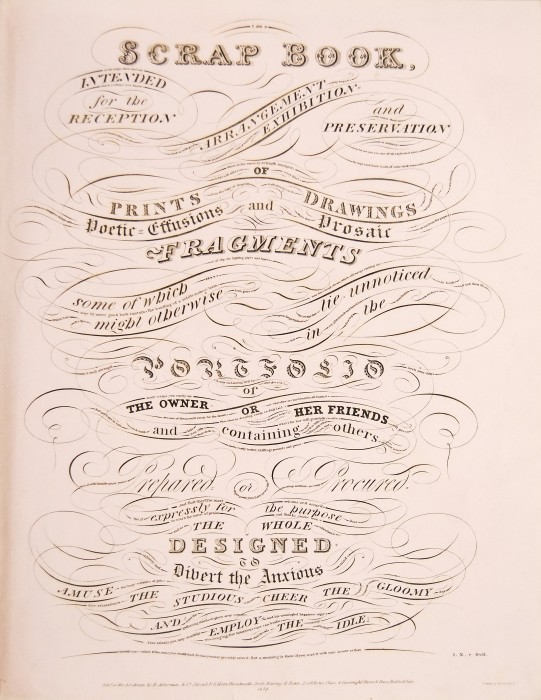

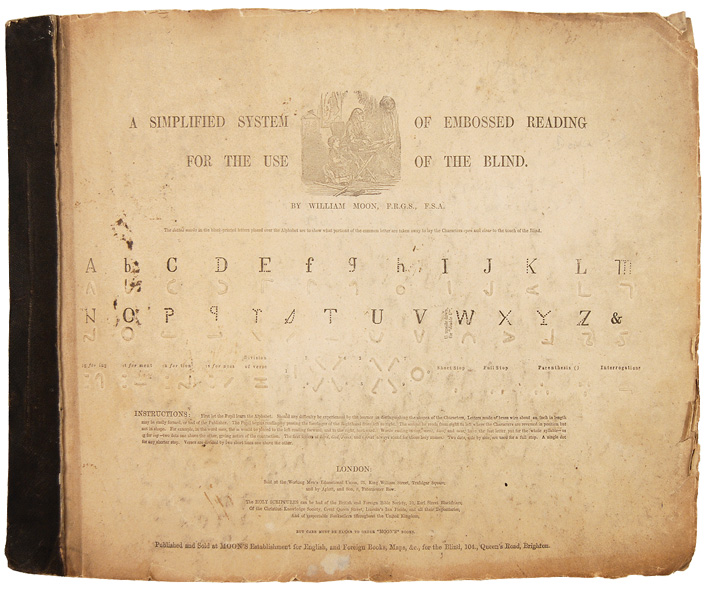

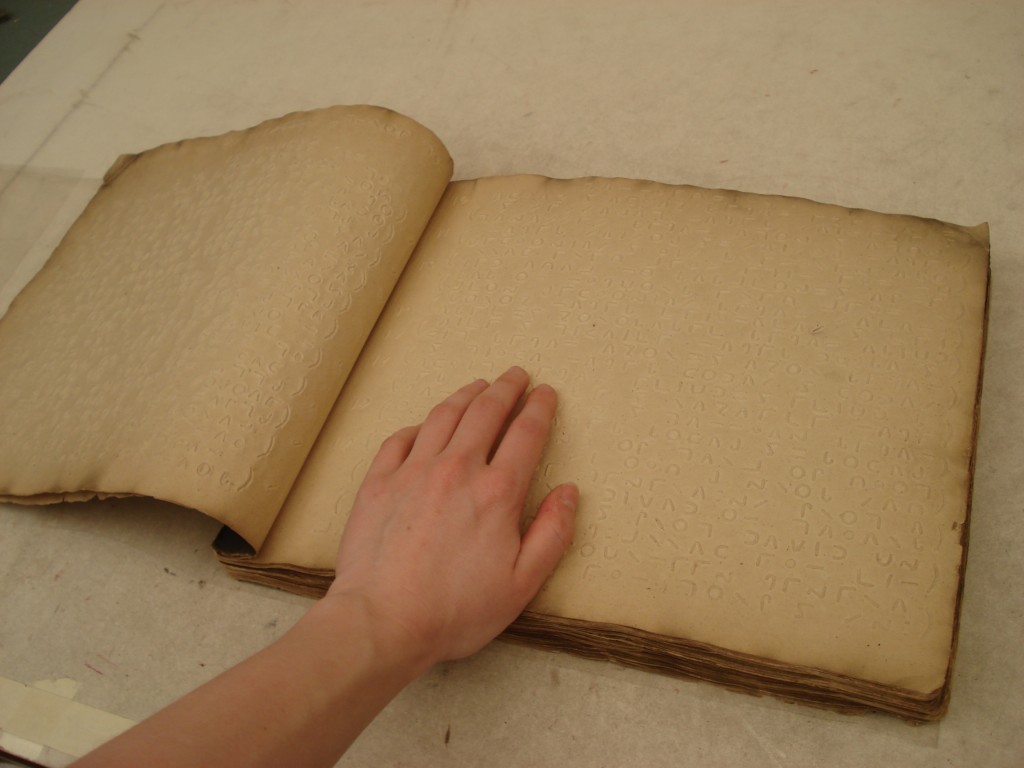

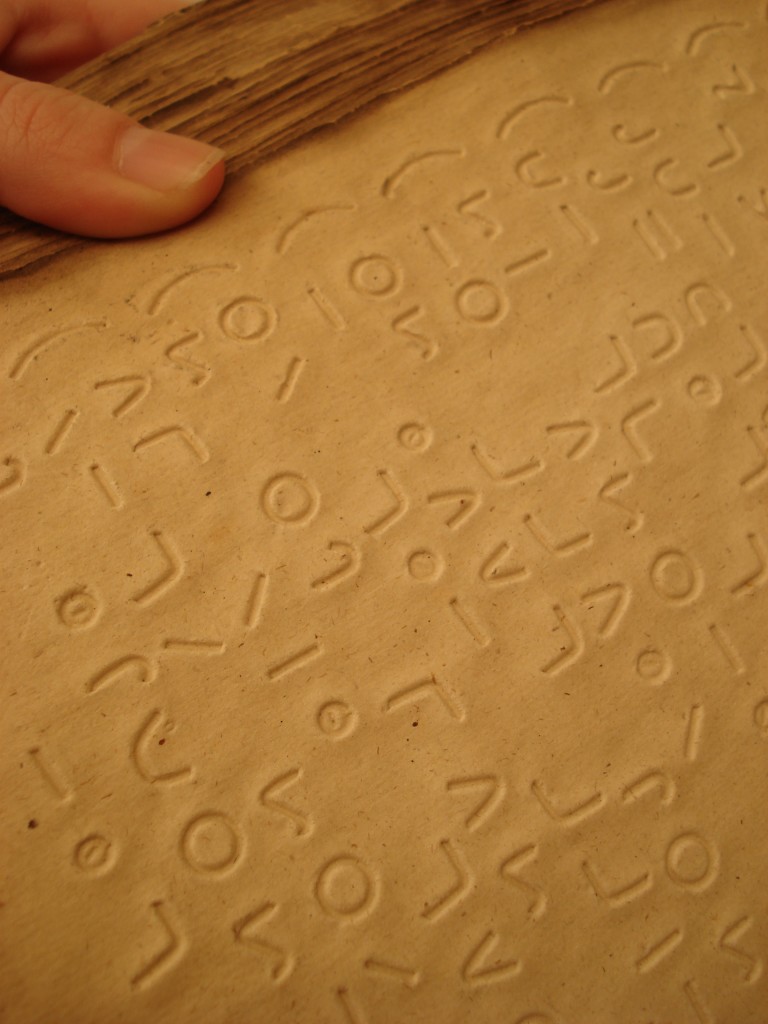

One of the most interesting parts of the book is the title page, itself an ephemeral item that was meant to be removed by the purchaser. It’s unusual to find one intact, and this example is a typographic masterpiece, weaving together a variety of typefaces including the tiniest I’ve ever seen forming decorative curls around the larger phrases.

Definitely click to enlarge!

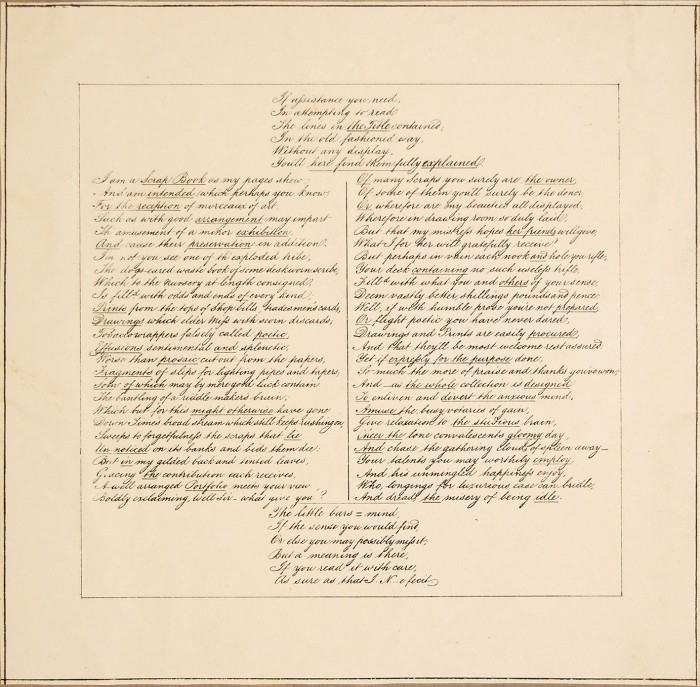

There’s also a guide, in case you can’t read the very tiny text!

It’s been pasted into the very back of the book.

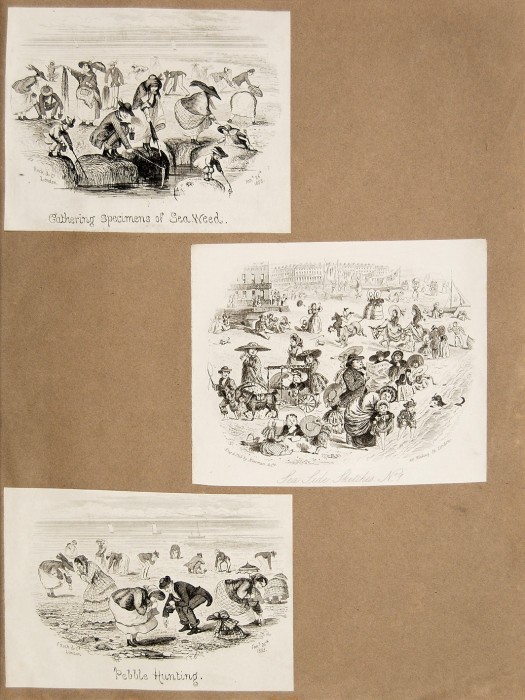

The contents of the scrapbook date from the end of the 1700s to at least the 1850s, with some items entered at the time of their publication and others culled from older books or periodicals. The compiler seems to have had an interest in fashion, devoting a number of pages to fashion plates, and in many cases cutting out individual figures and carefully combining them in hand-coloured vignettes, as below. This was a common practice of scrapbookers during the period.

Also popular with this compiler was a series of prints depicting South American people, produced by John Skinner in 1805.

Each individual and caption was delicately cut from the original print and pasted into the scrapbook.

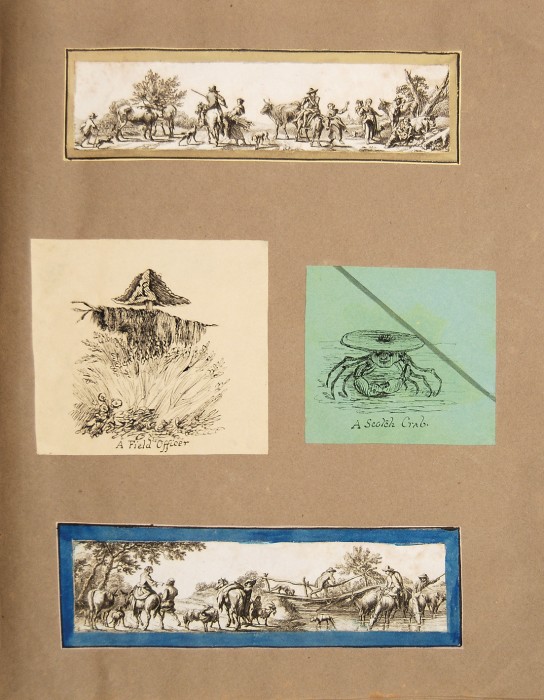

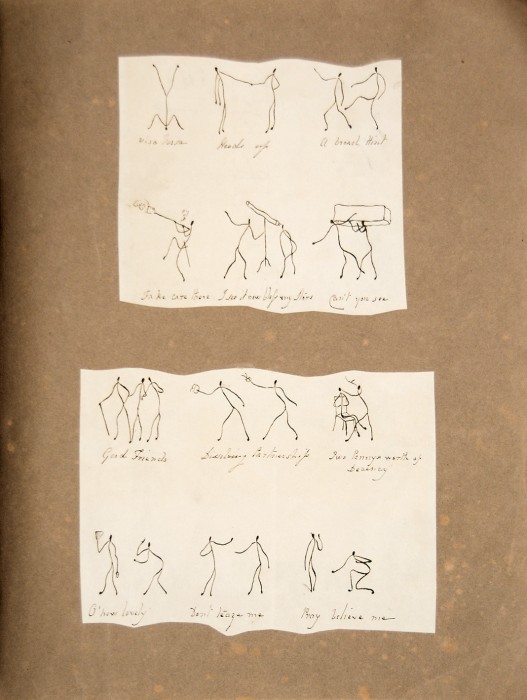

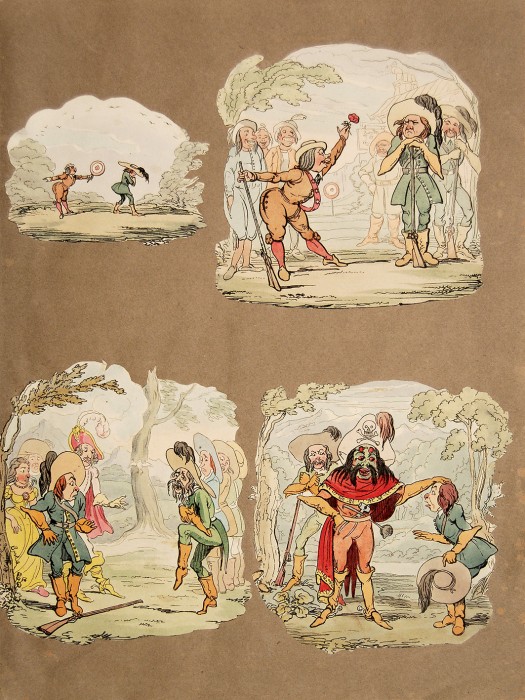

Either the compiler or a family member or friend was an amateur artist, and many pages are filled with humorous original sketches and visual puns.

The kind of innocuous things you can imagine as the result of parlor games, though that “scotch crab” is kind of freaking me out.

There are lots of engravings of tourist attractions and scenic areas. The borders around these have been hand-painted:

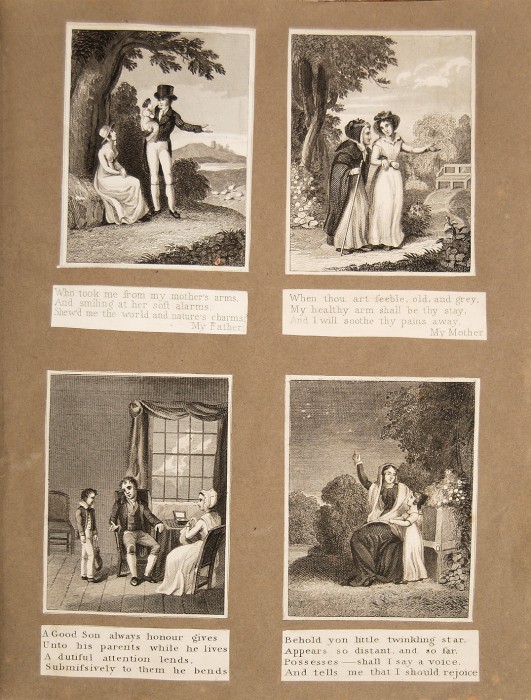

There are quite a lot of these very dull, very badly written, moralistic poems and vignettes. Was our compiler the Ned Flanders of the 1850s?

Then there are some entries that are more random – things that happened to catch the eye of the compiler. Like our strange wheeled friend above.

Scrapbooks, as well as being entertaining, are a great resource for understanding the viewpoints and leisure pursuits of middle and upper class women during the nineteenth century. I can’t help but wonder what historians of the future would make of the wall behind my desk, covered in postcards, clipped out comic strips, silly notes from colleagues, and the wrappers to French sweets.

Recent Comments