In January 2021, Fendi showcased its first womenswear collection under artistic director Kim Jones. Featuring marbled prints, androgynous cuts and floor-sweeping capes, the collection was in part inspired by Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, and her relationship to her long-time paramour Vita Sackville-West, as well as the work and life of the Bloomsbury Group and the productions of the Hogarth Press. Orlando, Sackville West’s son Nigel would later say, was “the longest and most charming love letter in literature, in which explores Vita, weaves her in and out of the centuries, tosses her from one sex to the other, plays with her, dresses her in furs, lace and emeralds, teases her, flirts with her, drops a veil of mist around her”. Playing with texture, gender and literary allusion, Jones’ collection is a fitting homage.

In an adjoining room of the opulent Palais Brongniart, where the show was held, an exhibition of rare books and manuscripts told the story of the Vita and Virginia’s romance, as well as the lives and loves of the wider Bloomsbury group. This exhibition was co-curated by Jones and Sammy Jay, literature specialist at Peter Harrington. A prolific collector of art and books, Jones has worked with Jay in recent years to put together an impressive collection of Bloomsbury material, inspired by a life-long passion for Woolf and her contemporaries. Growing up in Sussex, a stone’s-throw away from Charleston – the house which formed the hub of the lives and romances of the Bloomsbury group – Jones felt a magnetic pull towards the vibrant cast of characters who coalesced around the central figures of Virginia Woolf and her sister Vanessa Bell.

In the wake of the show, Sammy Jay describes the process of putting together this remarkable exhibition, and working with jones on his Bloomsbury passion project.

The exhibition at the Palais Brongniart

What is the story of your collecting relationship with Kim Jones? How did you meet?

Sometime in the winter of 2019, Kim walked into our shop on Dover Street in Mayfair, asking to see a special book that he’d spotted on our website: a first edition of Virginia Woolf’s Jacob’s Room inscribed to her sister Vanessa Bell (with its rare dust jacket, which Vanessa designed). It was immediately clear that here was someone who not only knew what they wanted, but also had a very strong relationship to books, both as cultural objects and as rarities. He walked out with the book that evening. I should stress that, with a book like that, you’re starting at the top.

When the first lockdown happened, our shops were closed, and Kim too was stuck at home with his books. During this time, we spoke regularly. It was great, really, to have someone enthusiastic to geek out with on all things Bloomsbury. Over the next year he really expanded his Bloomsbury collection, more than once confessing himself to be “a bit of a completist”. It’s been a delight helping him to collect an example of every single book printed by the Hogarth Press, and he has no qualms about acquiring more than one copy of the same book. For example, I was scouting at the New York book-fair and spotted something really fabulous – a first edition of Orlando inscribed by Woolf to Noël Coward. I knew Kim already had copies inscribed to Vita Sackville-West and Vanessa Bell, but I called him anyway and he said “yes please”. And why not? Unique items like that each tell a different story, and when you bring them together, they start to speak to each-other too.

Kim jones photographed on the runway of the Fendi womenswear collection, January 2021. Image: Fedi

Where did the idea for curating the exhibition come about? Could you speak more about the process of collaboration?

The idea for doing an exhibition of his books at the show was all Kim’s! It was around Christmas last year he asked if I could help curate it, and of course I was very excited. We had under a month to prepare, which made for an exhilarating process (the fashion world runs on a different clock to the rare book world, as perhaps you can imagine).

We spent a few evenings in his library discussing and finalising the overall selection – so much fun with all these priceless books and manuscripts spread out over the floor. It was a privilege watching him decide the aesthetic arrangement (Kim’s super-power) for the various marbled and patterned paper covers on the Hogarth Press books. We discussed the story we wanted to tell with the exhibition, and Kim was very clear that the focus should be on the formidable women of Bloomsbury: Virginia, Vita, Vanessa…

I must say it was a jaw-dropping moment when he first showed me the copy of Orlando that Virginia presented to Vita Sackville-West, who inspired, and to whom she dedicated, the book. This is what we would call in the trade “God’s own copy”, the best possible, indeed best imaginable, copy of any given book. All collectors are, whether they know it or not, on the quest for these biblio-grails, and, like the grail, very few ever get to see it.

For me, this book had to be in at the heart of the exhibition. So what took shape was a curation centring on Orlando, with a cabinet in in middle displaying Kim’s extraordinary proliferation of presentation copies, with Vita’s at the centre. On either side of this, I placed facing cabinets for Virginia and Vita – gazing on each-other, as it were, in mutual amazement – filled with magnificent examples of their books, letters, and manuscripts. Beside these were: a cabinet dedicated to Vanessa Bell and her contribution to the Bloomsbury aesthetic; one showcasing Kim’s exceptional archive of letters from Virginia Woolf to Clive Bell (with whom she was very close – he even proposed marriage to her before Vanessa); two displaying a range of early books produced by Leonard and Virginia at the Hogarth Press, with their striking hand-decorated covers; one for Roger Fry and the rare books produced by his short-lived Omega Workshops; and a final small cabinet dedicated to nostalgia, looking back at two new beginnings – the poetry anthology Euphrosyne which marks the beginning of the Bloomsbury group coming together at Cambridge, and the little brochure which Kim kept from his first ever visit to Charleston.

Why do you think the works of the Bloomsbury Group hold such a cultural resonance today?

It’s a good question – of course there’s the old joke about them “living in squares, talking in circles, and loving in triangles”, but for me the real story is that these were people who were deeply passionate about life and about art, and devoted themselves to getting to the bottom of both – that pursuit is surely not a theme which gets old.

It’s also key to acknowledge that the Bloomsbury group was exceptional in being a creative matriarchy – its leaders were women, the sisters Virginia and Vanessa being the twin geniuses at the heart of the group, and other major figures in the Bloomsbury orbit like Vita Sackville-West and Ottoline Morrel similarly held far more prominent sway than their husbands.

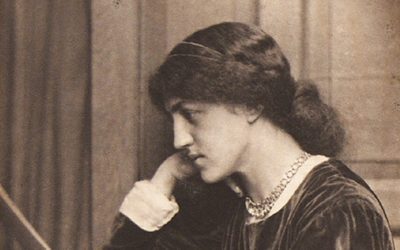

Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West. Image: Charleston

There’s a craft element of their practice which I think increasingly appeals to us as human beings caught in a mechanised and digitised world: the Hogarth Press was originally started as a sort of aesthetic therapy for Virginia to learn printing and practice book-binding, which she found “exciting, soothing, ennobling, and satisfying”. A lot of people have turned to amateur arts and crafts during this last distressing year. In Virginia’s case, look what extraordinary creativity was unlocked, not just for herself, by that first step!

What do you think connects the world of literature and fashion, aside from the obvious aesthetic qualities? Is there perhaps a philosophy that connects the two?

I certainly don’t pretend to be in touch with any fashion zeitgeist, though being introduced to the fashion world through rare books has been a fascinating, if unexpected, journey.

There are definitely compelling points of contact, most pertinently in Orlando itself, which has a lot to say about clothes and how “they change our view of the world and the world’s view of us”. I think the word “fashion” even appears in the first sentence of the book.

I was very struck when a friend told me that amateur costume drama was one of the frequent entertainments of life at Charleston. It makes sense! There is a sense in which all creative writing is inherently a form of dressing up; a writer must wear many guises to tell a story. Do the coats in our wardrobes and the books on our shelves serve to expand, in a similar way, our repertoire of selves? Perhaps literature, like fashion, is another way of becoming more than who we might otherwise nakedly be.

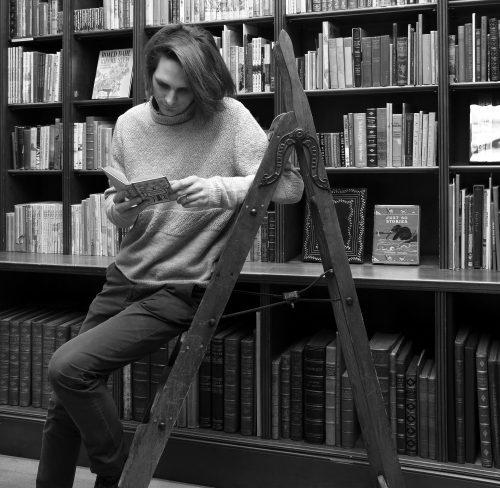

Sammy Jay, literature specialist at Peter Harrington Rare Books

The idea of collecting rare books and manuscripts as a creative and generative passion rather than an antiquated pursuit, is an important sentiment to you, why is this?

You’ve put your finger on it exactly! For me, Kim’s show was a world-class example of how collecting can be creative, how getting in touch with old things can give rise to new. This has always really mattered to me and inspired my approach to book-selling. At this point (I’m 32, and in the game now for almost a decade), I have to admit to myself that I’m committed to the rare book life, so it has been really gratifying to have been involved in something that revamps the inaccurate old image of book collecting as a dusty, desiccated pursuit. In my experience the rare book world is full of fascinating and fascinated people, dealers and collectors from all walks of life, each lured to the same spring in pursuit of whatever it is that they, deep down, care about most.

Is there a particular piece in the exhibition that you find exceptionally intriguing and/or inspiring?

One of the star Woolf items in Kim’s collecting constellation is an original manuscript she wrote for the introduction of Mrs Dalloway. It was written for a new edition of the book published in 1928. When it was first published three years prior, Mrs Dalloway had no authorial introduction, so this was in fact Woolf’s first opportunity to publish her own commentary on her ground-breaking novel, about which so much had already been said by the critics. Her handling of the book’s “theory” is wonderfully coy, but I love it most for the mind-bending sub-clause which Woolf adds to this sentence: “For nothing is more fascinating than to be shown the truth which lies behind those immense facades of fiction – if life is indeed true, and if fiction is indeed fictitious”. This was written in the same summer that Woolf was putting the finishing touches to Orlando, and offers, I feel, a glimpse of the enduring mystery at the heart of that book.