How did people learn how to cook in the 18th-century? Many might think that the answer is “at home with their parents”, but the methods of culinary education in the 18th-century were more diverse than one might imagine. Manuscript cookbooks from this time offer a treasure trove of culinary insights not found in their printed counterparts. Unlike printed books – often created by non-culinary authors and read as a form of entertainment – these handwritten manuscripts offer authentic glimpses into the dishes prepared and the techniques that were employed.

From about 1600 onwards, the most common type of cookery manuscript is the household cookbook, serving as repositories for recipes collected from family, friends, or transcribed from existing books. These intimate collections, reflecting the unique tastes of individual families, were never intended for public consumption.

We’ve recently encountered two rather unusual early 18th-century manuscripts which were instead produced for an audience, and which shed light on the period’s culinary landscape. They feature original recipes by the prominent chefs Edward Kidder, perhaps the best-known cookery teacher in London at the time, and Ralph Ayres, head cook at New College, Oxford.

Edward Kidder

Edward Kidder, a renowned culinary educator in London during the early 18th century, left a lasting mark on the culinary world. This manuscript, produced in his cookery school, is a rare example of a culinary textbook.

Kidder’ school of pastry and cookery was one of the earliest in England. According to Kidder’s obituary, he “taught some 6,000 ladies in his time” (Notes and Queries, p. 185), leading scholars to conclude that “a substantial number of London households of the time must have had Kidder-trained cooks” (Potter, p. 10). Around 1720, he published a guide for his students, Receipts of Pastry and Cookery.

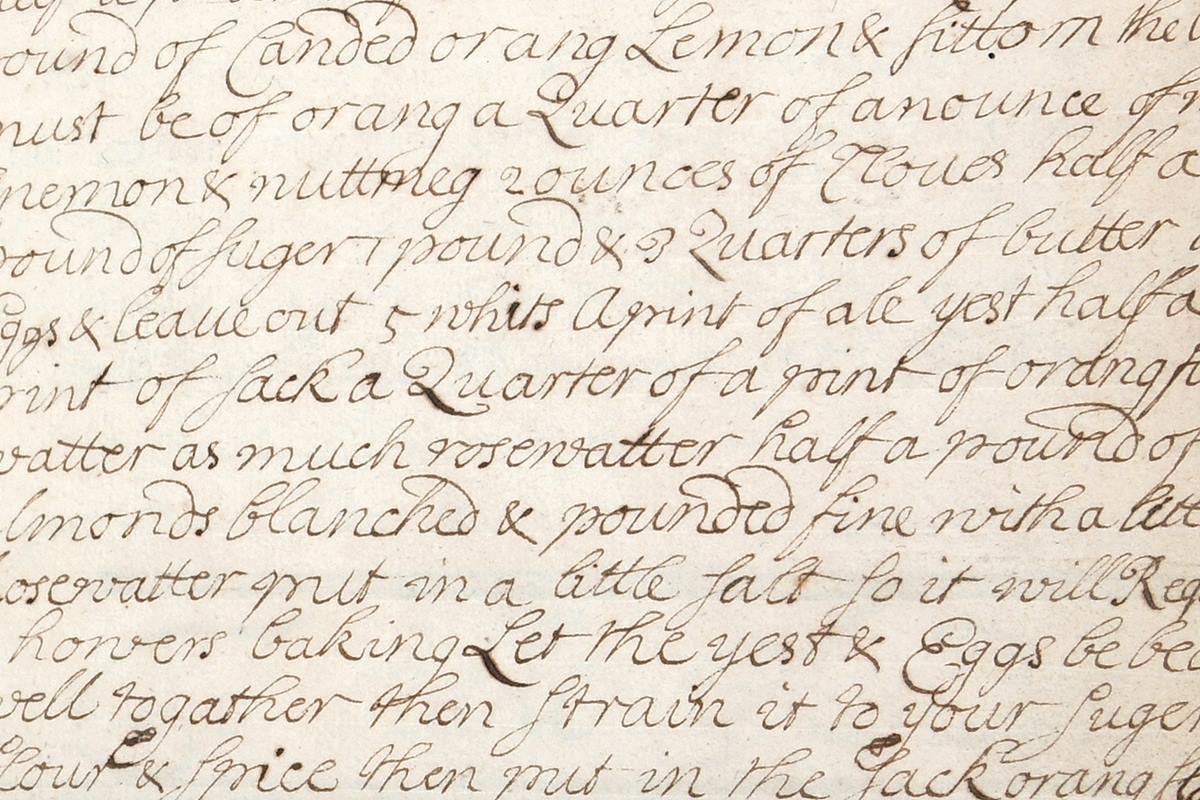

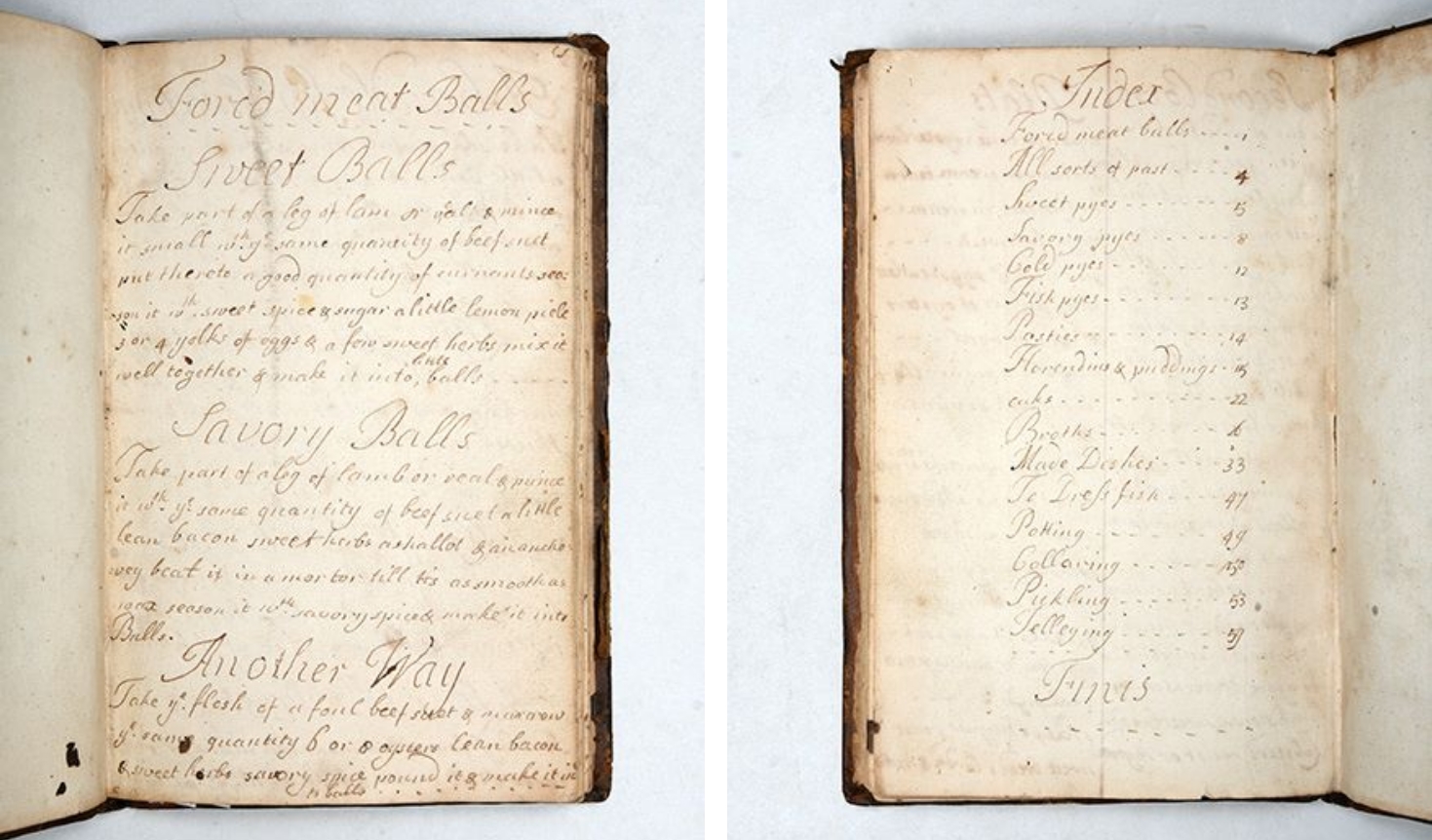

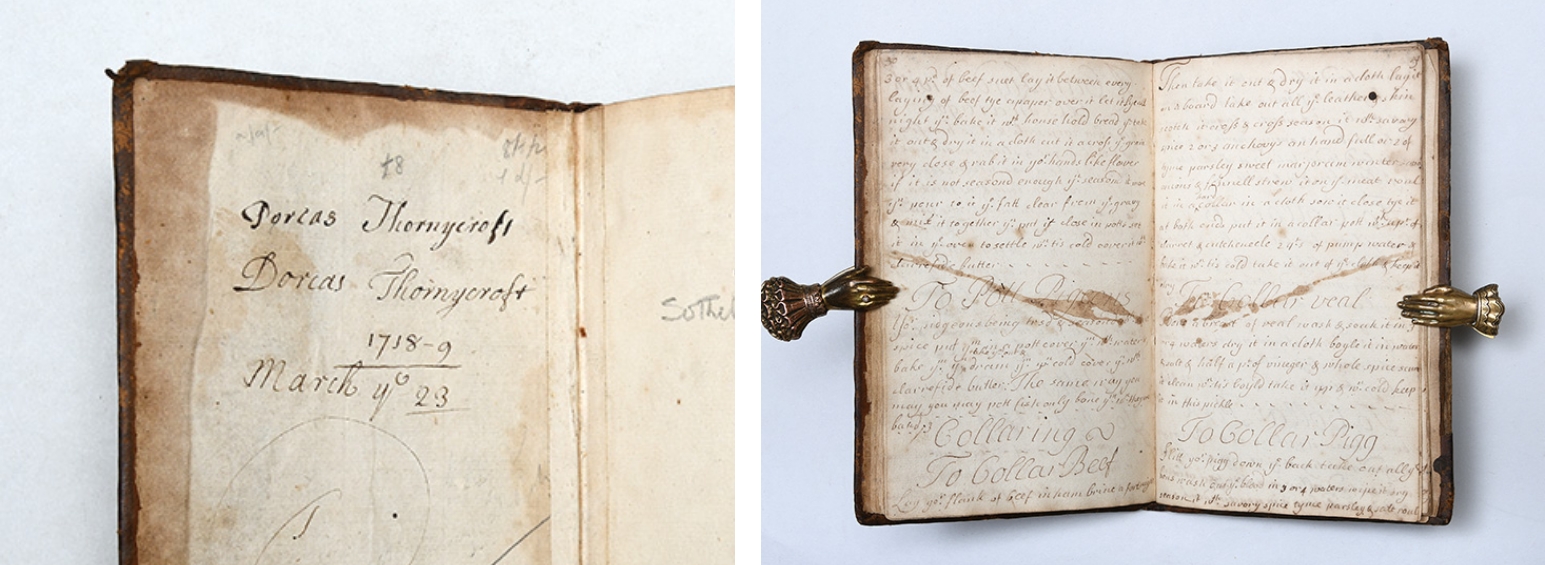

Before the printed edition came out (and indeed even after), his recipes had a wide circulation in small hand-written books: our manuscript is one of only eight known examples remaining. The contents are divided into chapters on meatballs, pies, broths, meat, fish, and poultry dishes, puddings, cakes, potting, collaring, pickling, and jellying.

Interestingly, some recipes or variants present here were not included in the printed edition. Among them, we find: “A Lambstone & Sweetbread Pye”, “A Green Pease Soop”, “A Batter Cake”, “A Bisk of Pidgeons”, and a few more.

But who wrote the manuscripts? Some scholars believe that Kidder provided blank notebooks to his students, who would then transcribe the cookbook “to reinforce its contents into their minds” (MSC). However, as the handwriting of the text often doesn’t match that of the ownership inscriptions (as in our case) and many examples are in a very similar hand, it seems plausible that some of them were transcribed by copyists and then provided to students at the beginning of their course, to be used during the practical sessions.

These manuscripts played a crucial role in Kidder’s teaching methodology, influencing subsequent generations of cooks, as evidenced by instances of plagiarism by renowned authors throughout the 18th century, including Mary Kettilby, Charles Carter, Robert Smith, and Sarah Harrison.

The present example belonged to Dorcas Thornycroft (c. 1690-1759), a landed lady of Kent, who inscribed her name on the front pastedown with the date “1718-9, March ye (the) 23”. The occasional stains (particularly in the section dedicated to fish, at pp. 46-51) indicate that she took Kidder’s classes very seriously.

Ralph Ayres

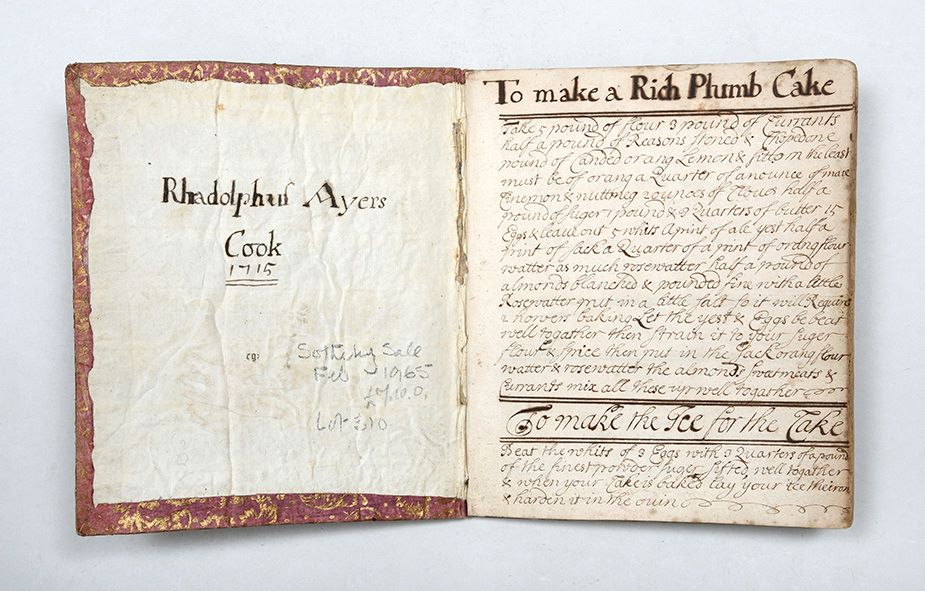

Delving into the life of Ralph Ayres, head cook at New College, Oxford, unveils another intriguing culinary narrative. We know him from a small number of manuscripts, all containing the same collection of recipes, charmingly written, and bound in similar flower-patterned paper. Our example is one of seven known, and one of the earliest.

The dates on the manuscripts indicate that Ayres was head cook at the college from c.1714 to at least 1722. The details of his life before becoming a cook are elusive – scholars tend to identify him with a wheelwright recorded in the parish registers of St Cross Church, who married in 1691.

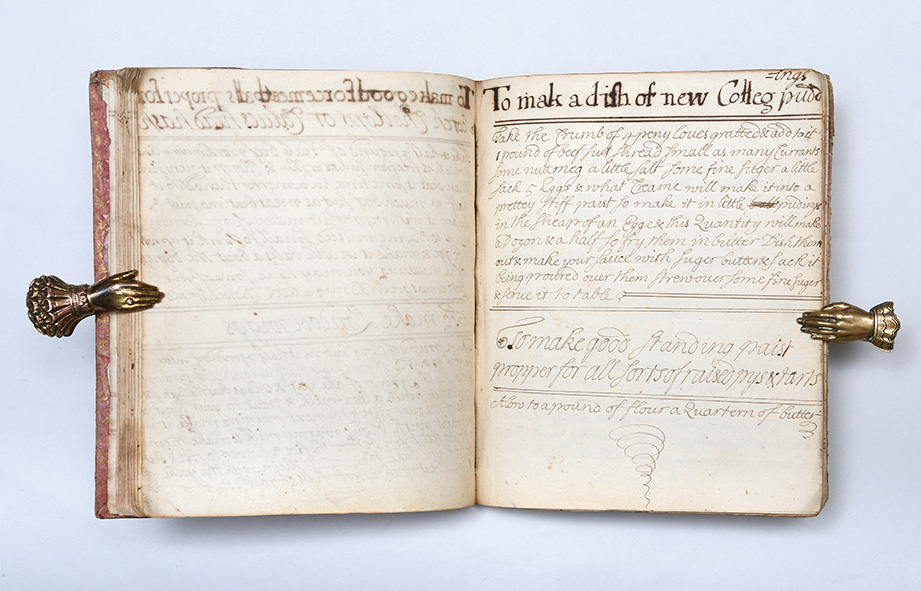

If the man is quite mysterious, his recipe collection is instead very well-known and formed the basis for meals at New College for decades. Reverend James Woodforde, remembering in his diary the menu of a private dinner with friends at the college in 1774, mentions many dishes appearing in Ayres’s book. One of them is the famous New College pudding, which is still occasionally served by the chef today, although the recipe has changed throughout the years.

The pudding is one of 70 recipes in this manuscript. Some of them are very traditional, including dishes now unfamiliar but with a long culinary history: we find the instructions for adding anchovies to a gravy, and a mention of “verjuice”, an acid condiment obtained from unripe fruit which originates from the Roman cookery book of Apicius. Other recipes are still popular today, such as Queen Cakes, Oxford sausages, gingerbread, and tarts (a recipe that a century later perhaps inspired Alice in Wonderland).

Ayres’s book was rediscovered in the 20th-century, when L. G. Wickham Legg found and published one of the manuscripts in 1922. A modern edition appeared in 2007, edited by Jane Jakeman and based on a different example. Comparing our manuscript with Jakeman’s revealed intriguing differences. Our example, 6 years earlier, features many recipes which were later excluded, including “To Candey Angelica Stalks”, “To make biscakes”, “To make a Tanzey”. It also contains a recipe titled “To make pancakes courtfashen”, which reoccurs almost identical in the 1721 manuscript as “To make Ayres his pancakes”. They must have been so delicious and frequently requested that the recipe eventually became known as “Ayres’s” version.

The standardised contents and attractive production of Ayres’s manuscripts suggest that they were not personal working-cookbooks; the absence of prominent cookery stains or corrections in our example supports this idea. Instead, they appear to be items made especially made for other readers to enjoy, perhaps given by the cook as gifts to his friends.

The significance of Kidder’s and Ayres’s manuscripts extends beyond the recipes themselves, offering valuable insights into the transmission of culinary knowledge. They allow us to connect with the past and gain a deeper appreciation for the culinary traditions that continue to shape our tables today.

Written by Alessia Colombo

Bibliography

- David Potter, “Some notes on Edward Kidder”, PPC, vol. 65, 2000

- Jane Jakeman, Ralph Ayres’s Cookery Book, 2006

- L. G. Wickham Legg, A Little Book of Recipes of New College Two Hundred Years Ago, 1922

- Manuscript Cookbooks Survey 183

- Notes and Queries, vol. VII, Mar. 1895

- Peter Targett, “Edward Kidder: his book and his schools”, PPC, vol. 32, 1989

- Simon Varey, “New light on Edward Kidder’s Receipts”, PPC, vol. 39, 1991