by Sammy Jay.

Collecting literature of the Great War has never been so timely. After the recent centenary commemorations, the war has acceded into the halls of History proper, and yet at the same time, with the minds and memories of the nation cast back, it has also regained some presence. This, combined with an ever-mounting interest in old books (and their possible value), will no doubt send families rifling through their attics, uncovering who knows what treasures. We can also expect with confidence a good four years’ worth of Great War auctions and bookseller’s catalogues. The market, both in supply and demand, should swell. So, with the time ripe, the questions are: why is this area of collecting particularly interesting, and what should one be looking out for?

One particularly appealing aspect of the literature of the Great War is that it presents an intersection between the “soft” forces of Literature and the “hard” forces of History, affording even its minor voices a degree of dignity (as well as documentary interest in that “they were there”), unafforded to, say, Martin Amis or Will Self, however distinguished their writing.

It is also true, perhaps partially for this reason, that a great deal of war writing (particularly poetry) did get published during and in the two decades following the war. Indeed, when a publisher could not be found, it nonetheless became a very common practice for the families of killed soldiers (usually officers it must be said) to resort to privately printed editions of their poems done in small numbers for distribution among friends and family. These can be intriguing, evocative, and rare.

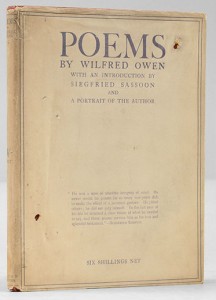

Materially, there is much in play to recommend Great War literature to a collector. Production standards during and immediately after the war made things fragile, so poor copies might be numerous and cheap but really nice ones uncommon and highly desirable. Dust jackets can also be very scarce on books from this period – in the 1910s and 20s, jackets were still usually discarded and point of sale, and any that have been retained, let alone survived the intervening century in any condition, also add a great deal of value. Wilfred Owen’s Poems (1920) is a particularly covetable example in the jacket, and for the same reason a first edition copy without the jacket would satisfy many collectors. In this way, too, the market presents a broad and appealingly accessible range of goods and prices.

There must also be an added appeal in finding any book that was actually in the trenches – these gain the resonance of a relic. The supreme example of this must be the mud-spattered war diaries of Siegfried Sassoon, held at the Cambridge University Library and recently digitised for public perusal, but there must be more out there.

Great War literature is therefore an excellent market for collectors of any budget, with a number of rare and desirable high-spot items rearing out of a muddy sea of highly variegated material, much of which is still inexpensive, yet remains highly interesting.

Here, with some brief biography, are the authors and titles you might start with:

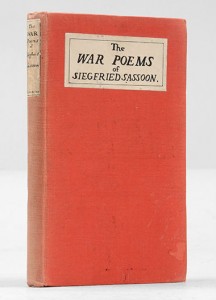

Siegfried Sassoon (1886-1967) entered the war as an already published poet, with at least twelve small edition of his verses having appeared before 1914 (from the privately printed Poems (1906) to The Daffodil Murderer (1913), published under the pseudonym Saul Kain). He entered the war as a sportsman and patriot, winning the Military Cross for his acts of bravery, yet within three years became the most vociferous and high-profile opponent of its aims. His first wartime collection was The Old Huntsman (1917), published while convalescing in London from a war wound. It was at this time that he made his famous “Soldier’s Declaration”, a “wilful defiance of military authority” criticising the “political errors and insincerities for which the fighting men are being sacrificed”, sent as a letter to his Commanding Officer, with copies distributed to notable figures including Thomas Hardy, Eddie Marsh (Churchill’s Private Secretary) and H. G. Wells. It was soon published in The Times, and even discussed in the House of Commons. Sassoon was swiftly sent to Craiglockhart Hospital, saved from the firing squad by an excuse (made for him at Robert Graves’s instigation) of shell shock. He did return to the war, only to be wounded out again, and published his second “savagely realistic” war collection Counter-Attack around the time of the Armistice, November 1918. This was shortly followed by War Poems in 1919, considered his definite collection.

Sassoon continued to have a colourful literary existence long after the war, and published many more collections, though perhaps the text for which he is best remember is Memoirs of an Infantry Officer (1930), the second part (dealing with the war) of his three-part autobiographical novel, now known as the “Sherston Trilogy” after his protagonist George Sherston. Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man (1928) and Sherston’s Progress (1936) would complete the set. Other suggestions might include J. C. Dunn’s privately printed The War in the Infantry Knew (1938), a valuable and elusive compilation of about 50 war reminiscences from members of the Royal Welch Fusiliers (which included both Sassoon and Robert Graves), including a chapter by Sassoon. His later collection Road to Ruin (1933) might make a fair point of closure, with Sassoon’s poems warning of the future war – the first edition even includes an epigraph by Albert Einstein.

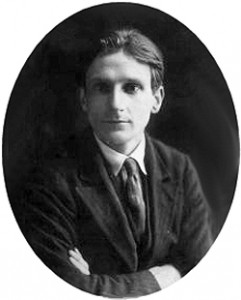

Wilfred Owen (1893-1918), now generally considered the poet laureate of the Great War, wrote the definitive “Dulce et Decorum Est” and “Anthem for Doomed Youth”, and remains popular today for his highly affective language. However, when he met Siegfried Sassoon while both were convalescing at Craiglockhart Hospital, Owen was still unpublished and considering giving up poetry. It was Sassoon who encouraged him, and indeed first put him into print, with his poem “Song of Songs” appearing in the legendarily rare 1st September 1917 issue of the hospital magazine “Hydra”, edited by Sassoon. After Owen died just one week before the Armistice, Sassoon collected Owen’s poems in the 1920 volume Poems – a necessary addition to any Great War Poets collection. For those seeking a more accessible copy, the 1931 expanded second edition, containing new unpublished Owen poems and an introduction by Edmund Blunden, is a good option.

Robert Graves (1895-1985) is one of the longest lived most prolific writers of the 20th century, but he saw his literary beginnings in the trenches alongside Sassoon in the Royal Welch Fusiliers. His wartime collections are his very first collection Over the Brazier (1916), followed by Fairies and Fusiliers (1917). He is best remembered for his still-popular autobiography Goodbye to All That (1929), which is the only explicitly WW1-related book in Connolly’s 100 Key Books of the Modern Movement. There is a desirable and interesting issue point to look out for with this title – the first issue copies contained the first appearance of “Dear Roberto”, a fearful and touching poem written as a verse-letter Graves by a shaken Sassoon from his hospital bed just before the Armistice. Graves included the unpublished poem without the permission of Sassoon, who swiftly called for the book’s suppression. Later copies were issued with these lines erased, and only a few copies of the first issue got into circulation. Graves also wrote many books not related to the War, such as his Roman Empire novel I, Claudius (1934), and, as an intriguing side-light, Lawrence and the Arabs (1927), Grave’s study of T. E. Lawrence (“Lawrence of Arabia”), whom he befriended at Oxford University after the war.

Edmund Blunden (1896-1974) published two collections during the war, Pastorals and The Harbingers, both in 1916, but the poems were all written before he went to the front, joining the Royal Sussex Regiment. He served at Ypres and the Somme, but survived without physical injury (a miracle he put down to his small stature, making “an inconspicuous target”). At Oxford after the Armistice he befriended Graves, and soon after met Sassoon. With the latter’s encouragement, he published his first true “war poetry” collection, The Waggoner (1920), followed by The Shepherd (1922). Between 1924 and 1927 he was Professor of Poetry at the University of Tokyo, but returned to England in 1927. In 1928 he published his war memoir Undertones of War, which is a valuable resource, and made him a respected voice of remembrance, as reflected in one verse and one prose anthology or war writing, An Anthology of War Poems, and Great Short Stories of the War, in 1930. In his later life he cemented his position as a literary authority, editing collections and critiques of other poets, and ended as Professor of Poetry at Oxford University.

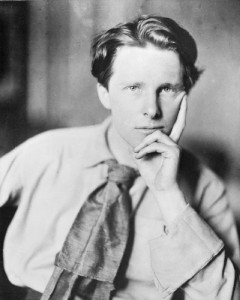

Rupert Brooke (1887-1915) was the most prominent member of the “Georgian Poets”. (Eddie Marsh’s Georgian Poetry series, published in five volumes 1911-22, gives excellent context to the literary landscape during and around WW1.) Brooke is remembered first for his having been “the handsomest young man in England” (W. B. Yeats), and for his sequence of five patriotic but nonetheless brilliant sonnets which included “The Soldier” (“If I should die, think only this of me…”). These were first published in the Dymock Poets’ short-lived magazine New Numbers (among poems by Lascelles Abercrombie, John Drinkwater & W. W. Gibson), all four numbers issued in 1914. Brooke’s poems were then taken up in a swell of patriotic fervour in early 1915, when they were printed in The Times Literary Supplement on 11 March, and then “The Soldier” was read from the pulpit of St Pauls Cathedral on Easter Sunday. By the point Brooke had already sailed with the British Mediterranean Expeditionary Force, on its way to Gallipoli, and on 23 April he died from an infected mosquito bite on the isle of Skyros in the Aegean. Brooke’s poetic fame was then secured by the hugely popular collection 1914 & Other Poems, first published May 1915. It includes the famous five sonnets as well as other war-related poems, making it a necessary addition to any Great War Poets collection and, in its romantic enthusiasm, constitutes a fair counterweight to the darker, more broken expressions of Sassoon and Owen. A scarce and romantic record of Brooke’s death (BOOK SOLD) was published in 1917.

These are merely five of the most famous names among the many Englishmen writing from within the Great War. An appealing anthology with which to pick up some of the lesser voices are A St. John Adcock’s For Remembrance. Soldier Poets, Who Have Fallen in the War (1918), and one shouldn’t miss Isaac Rosenberg’s Poems (1922), or Cecil Lewis’s classic flying memoir Sagittarius Rising (1936). Verses of a V.A.D. (1918), the only poetry collection by Vera Brittain (author of the popular memoir Testament of Youth, 1933), is excellent on the war experiences of female nurses. And there are important war novels in Frederick Manning’s Her Privates We (1930), which was preceded by the scarce unexpurgated version entitled The Middle Parts of Fortune (1929), and in American Humphry Cobb’s Paths of Glory (1935) – the basis for Kubrick’s 1957 film starring Kirk Douglas.

A collection should certainly be balanced by some books from the German side – the most obvious addition would be Erich Maria Remarque’s essential novel All Quiet on the Western Front (1929, originally published as Im Westen nichts Neues in January of the same year).

Conscientious Objectors must be taken into account, and of course one can always give context to the literature with accounts from a military perspective, as well as contemporary trench maps, photographs, army lists and general ephemera. Indeed, the breadth to which one might wish to extend a Great War collection is itself a compelling testament to the deep and wide-reaching effects of that conflict.