Annie Besant and Marie Stopes

By Thea Hawlin

In 1877 a woman stood up in a courtroom and became the first female to publicly endorse the use of birth control in the United Kingdom. The Freethought Publishing Company were being prosecuted using the Obscene Publications Act for issuing a pamphlet on contraception. The woman who defended the writing was Annie Besant. She argued that birth control had the power to alleviate poverty. No one listened. The next year her own essay The Law of Population was published: she kept talking.

Besant risked a lot by authoring her essay. In the wake of its publication her ex-husband claimed her radical views made her unfit as a mother. He won the case and Besant was separated from her daughter. The experience was excruciating, and one that saw Besant dedicate her life to “cure the pain at my own heart by soothing the pain of others”. She openly dedicated her work to the poor, specifically mothers “that it may make their lives easier”. In fact the most compelling argument within her essay revolves around her concern for the increased rate of “prolapsus uteri, or falling of the womb” in poorer communities, due to poor women being unable to rest after giving birth and returning to work immediately to feed growing families. For Besant the conditions of poverty were linked inextricably with a lack of choice with regard to reproduction, consequently her argument for contraception focused on how it was better to prevent birth than watch the living suffer. It’s an advocacy for contraception rooted from a place of fear, but also one specifically targeted at the working class in a somewhat uncomfortable way. Some of her views are unambiguously problematic: to say her comparisons of the poor to unchecked rabbits or insects feel jarring is an understatement. For her, having many children was a luxury that the poor couldn’t afford.

BESANT, Annie. The Law of Population: Its Consequences, and Its Bearing upon Human Conduct and Morals. One hundred and fifty-fifth thousand. London: Freethought Publishing Company, 1889.

However uncomfortable, Besant’s work highlighted the vast chasm of experience between those wealthy enough to nurture families and those too poor to do so. Health was a class matter, just as it is today with the privatisation of the NHS and American health insurance. Parallels with the one-child policy in China and the rolling back of reproductive rights in the US show us just how conflicted a modern outlook on population control and contraception are even today. A lot has changed since Besant wrote her essay, yet many of the concerns she addresses have remained resolutely unchanged. She notes herself how a system of complete control on who is deserving to reproduce, and when, would merely: “replace one set of evils by another”.

Though areas of her thesis remain dubious – one method of contraception she advocates involves a wad of cotton that can be replaced as easily as “an old slipper” – Besant busts important myths of the time, including the idea that nursing a child prevented the conception of another, as well as highlighting the dangers of abortion – at the time an unregulated and often risky procedure. As she notes “surely the prevention of conception is far better than the procuring of abortion.” It’s the key argument that pushes her polemic forward. She is perhaps a little too optimistic; theorising that with contraception “the root of poverty would be dug up”. Though she was against abortion she clarified that preventing conception was not morally evil: “an extraordinary confusion exists in some minds between preventive checks and infanticide. People speak as though prevention were the same as destruction.” Again, it is an argument that rages on in contemporary societies. Besant assured her readers “no life is destroyed by the prevention of conception, any more than by abstention from marriage”; a progressive argument that established a framework whereby contraception could be seen in a positive light.

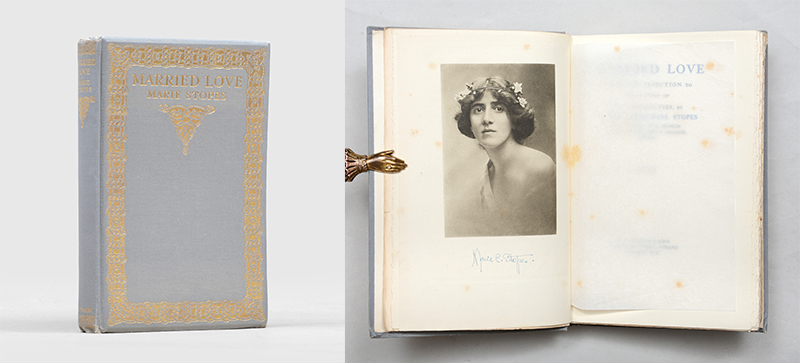

Following in Besant’s footsteps in 1918 Marie Stopes published Married Love, a book so popular it would be reprinted nineteen times. The first female academic on the faculty at Manchester University, Stopes also edited Birth Control News, a newsletter which gave explicit practical advice, and went on to found the first birth control clinic in Britain; a foundation bearing her name, which offers women support in their reproductive health, continues to this day. The first manual of its kind, it sought to rectify the wrongs she had suffered in her first marriage. The book was a means of saving others from divorce: “to increase the joys of marriage, and to show how much sorrow may be avoided.” Information which “may save them years of heartache and blind groping in the dark.” Controversially, Stopes advocated the use of birth control within marriage.

She opens the book: “more than ever to-day are happy homes needed”. Today, with growing divorce rates, some of Stopes’s words sound just as relevant for newlyweds: “It is never easy to make marriage a lovely thing; and it is an achievement beyond the powers of the selfish, or the mentally cowardly. Knowledge is needed, and as things are at present, knowledge is almost unobtainable by those who are most in want of it.” Her assertions are astute: “They ask: Is not instinct enough? The answer is: No, instinct is not enough. In every other human activity it has been realised that training is essential”.

Despite dated ideas and references (a point made especially uncomfortable knowing Stopes was a supporter of eugenics), the book does offer advice as kindly and lyrically as it can. There’s often a poetry to the way that Stopes writes about marriage and love: “The search for a mate is a quest for an understanding soul clothed in a body beautiful, but unlike our own.” It still feels at least partially accurate. The famously dubbed “honeymoon phase” is instead a “celestial intoxication”. The text itself is peppered with glorious metaphors, sex compared to everything from music lessons: “Only by learning to hold a bow correctly can one draw music from a violin” to electricity: “To use a homely simile – one might compare two human beings to two wires through which pass electric currents. Isolated from each other the electric forces within them pass uninterrupted along their length, but if these wires come into the right juxtaposition, the force is transmuted, and a spark, a glow of burning light arises between them. Such is love.” She identifies hormonal “sex tides” in women and openly rejects the idea that sex should be for men’s pleasure alone: “The supreme law for husbands,” she writes, is to “remember that each act of union must be tenderly wooed for and won, and that no union should ever take place unless the woman also desires it”.

These early works are compelling examples of how instrumental the voices of women were in creating a dialogue around birth control and how crucial they were in transforming the climate of that conversation. The discourse of sex and the teacherly pragmatism with which both approach their subject are prime examples of how woman’s voices were essential in normalising the narrative around the control of their bodies, but also vital in recognising female voices as worthy of a place within that conversation. For Besant contraception was a political issue that has radical implications for society at large. For Stopes it was personal, a vital part of sustaining a healthy and happy relationship in which both parties are equal. Contraception is revealed ultimately as an issue of addressing power dynamics, a means of establishing control, both within the domestic sphere and beyond it.