Truly Festive Children’s Stories

The magic and wonder of Christmas for many readers starts with the classic Christmas tales that we read as children and the adaptations of those stories that we see on our television screens every year. However, it is with classic children’s Christmas books that we first find much of the imagery and many of the traditions that we have come to associate with the festive season.

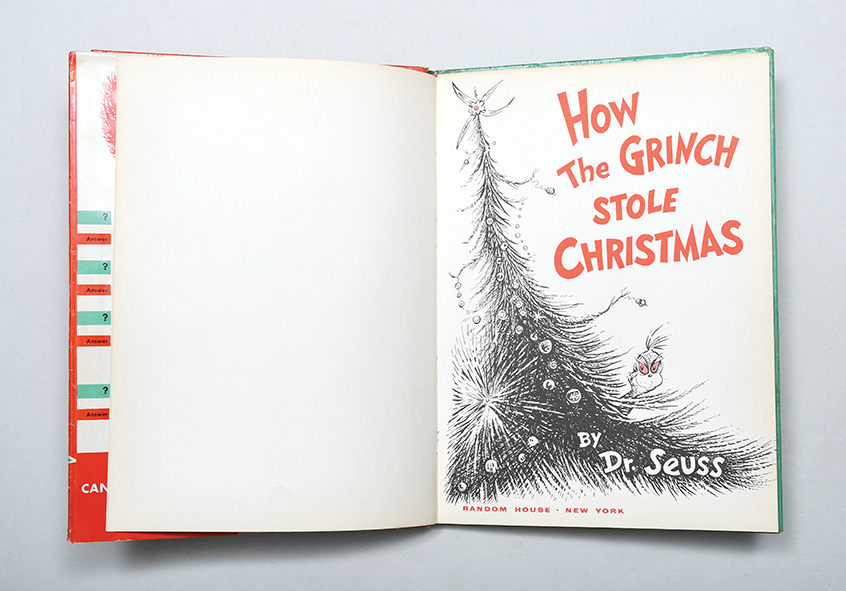

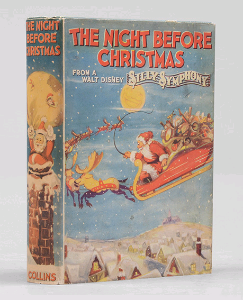

Walt Disney, The Night Before Christmas, 1934

Indeed, it is perhaps in celebration of these beloved Christmas stories, full of presents and treats and delights, that so many of the best-loved examples of children’s literature are essentially Christmas stories. For many children, Christmas is what creates a sense of magic and wonder in their imaginations and, through gifting, helps to instil a love for great books.

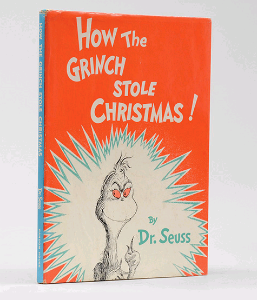

Does this help to explain the extraordinary longevity and emotive freshness of so many Christmas books? How is it that Raymond Briggs’s The Snowman or Father Christmas command such a special place not only with children but our own nostalgia for this time of year? Why is it that the opening lines of Clement Clarke Moore’s A Visit from St. Nicholas fill us with such warmth? We delight in the brash antics and uncouthness of the Grinch, and Dr.Seuss’s illustrations for How the Grinch Stole Christmas are every bit as iconic as the classic image of Santa Claus; a naughty, impish counterpart to the gentle, kindly figure of Father Christmas.

Dr. Seuss, How the Grinch Stole Christmas, 1957

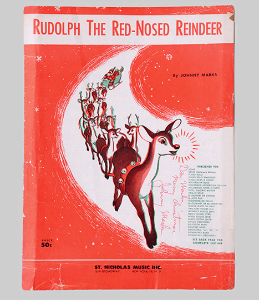

You cannot mention Santa Claus without bringing up his most famous and beloved compatriot Rudolph the Red Nose Reindeer. Noticeably absent from the roll call of magic reindeer named in Clement Clarke Moore’s poem, Rudolph is a later addition who quite literally outshone Comet, Dasher, Blitzen and company. In 1939, Robert L. May wrote a little story for an in-store Christmas promotional giveaway. The department store was called Montgomery Ward: the story was called Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer. Two and a half million copies were distributed that year alone, when in 1949 Johnny Marks wrote the famous song about the reindeer who saved Christmas.

The first printing of the Rudolph sheet music inscribed “Dear Marlin, Merry Christmas, Johnny Marks.”

While Robert L. May is responsible for creating Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer; where does our modern conception of Santa Claus come from? The image of the jolly Saint Nick with his sack full of gifts, arriving on Christmas Eve on his sleigh drawn by flying reindeer owes much to Clement Clarke Moore’s, A Visit from St. Nicholas. When it comes to Christmas there is arguably no more memorable line than: “Twas the night before Christmas, when all through the house, Not a creature was stirring, not even a mouse.” Not only was this poem largely responsible for many of the conceptions regarding Santa Clause from the nineteenth century on, but it also had a massive influence on popularising the tradition of gift-giving at Christmas.

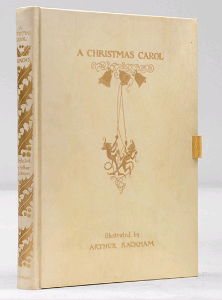

A Christmas Carol is without question the most famous and well-regarded Christmas story of them all and the story of Ebenezar Scrooge’s redemption and turn toward good has been adapted countless times with both the Muppets and the Flintstones, among other children’s favourites, offering their versions of the classic Christmas tale. While not written as a story for children, Charles Dickens’s novel, much sought after by collectors, has become such an enduring classic that it has transcended its original shape to become a story for all ages celebrated and retold again and again each year.

A Christmas Carol, illustrated by Arthur Rackham, 1915

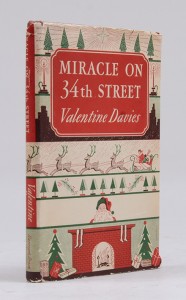

By 1947 the modern conception of Santa Claus that we have become familiar with was almost fully formed. The white beard, red clothes, reindeer with sleigh festooned with toys. This modern depiction owes much to Valentine Davies’s screenplay and subsequent novelization for Miracle on 34th Street. Davies wrote a 120-page novella after completing the screenplay for the original 1947 film which went on to be adapted multiple times most notably by John Hughes in 1994.

Valentine Davies, Miracle on 34th Street, 1947

Many of our favourite Christmas stories are films, however, a vast majority of these Christmas films on based on or inspired by early books and short stories. The most notable example of this is It’s a Wonderful Life, the beloved classic starring James Stewart. Based on the short story, The Greatest Gift, by Philip Van Doren Stern, originally self-published as a booklet in 1943 before being published as a book in December 1944, with illustrations by Rafaello Busoni. The story itself was loosely based on A Christmas Carol and owes much to Dickens’s original work.

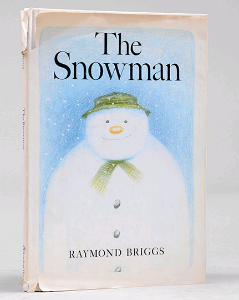

Other great Christmas stories continued regularly to be written, published, animated and filmed. New classics like Raymond Briggs’s 1978 book and, still astounding, animated masterpiece, The Snowman. A tear-jerking and beautiful tragedy that manages to celebrate the joy and magic of a boyhood dreamscape, the wonder in a child’s heart at the glory of those special days—friendship and love and togetherness—and yet hides none of the bitter sorrow and sadness which mark the passing of years, the loss of fleeting moments. Those who were with us once but are missing now. The Snowman was one of those creations which seemed timeless and eternal from the very start.

Raymond Briggs, The Snowman, 1978

Every year studios big and small put out Christmas movies good and not so good, and every so often a diamond emerges from the glistening paste. One such masterpiece which, like The Snowman, seemed timeless from the get go, was The Polar Express. The film was nominated for 3 Oscars but the 1985 book by Chris Van Allsburg, upon which the film was based, had gone one better having won the prestigious Caldecott medal for best children’s illustrated book of the year. The Polar Express exemplifies perfectly that quality which links so many of these enduring publications and the motion pictures that walk with them hand in hand. The quality of wonder, of magic, of the purity of childhood faith. It ends:

“At one time, most of my friends could hear the bell, but as years passed it fell silent for all of them. Though I have grown old, the bell still rings for me, as it does for all who truly believe,”

Recent Comments