The Scientific Renaissance

Two coincident events have been credited with sparking the scientific Renaissance. The Fall of Constantinople in 1453 accelerated the rediscovery of ancient scientific texts, while the invention of Gutenberg’s printing press made it possible to produce accurate copies of those texts, without the errors that hand-copying tended to introduce.

Within a hundred years, works that had previously circulated only in manuscript became much more readily available to the literate public, allowing the fruitful rediscovery of the scientific knowledge of the ancient and medieval writers.

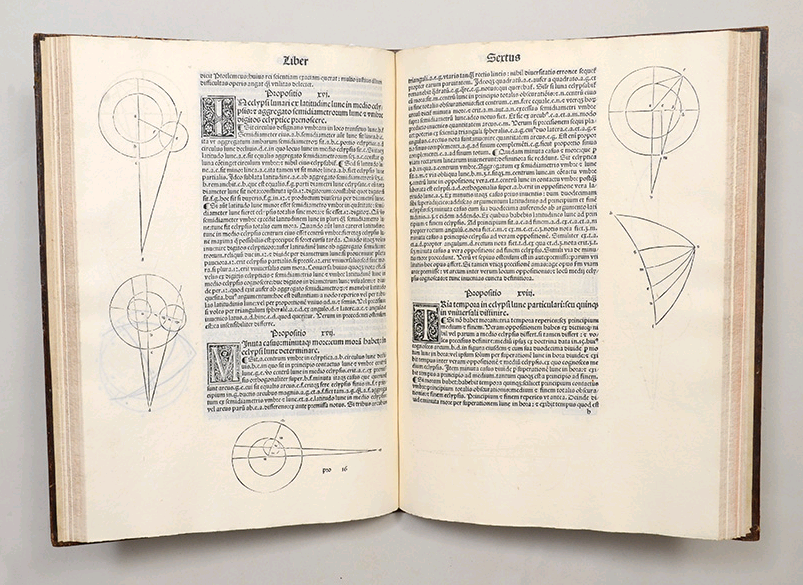

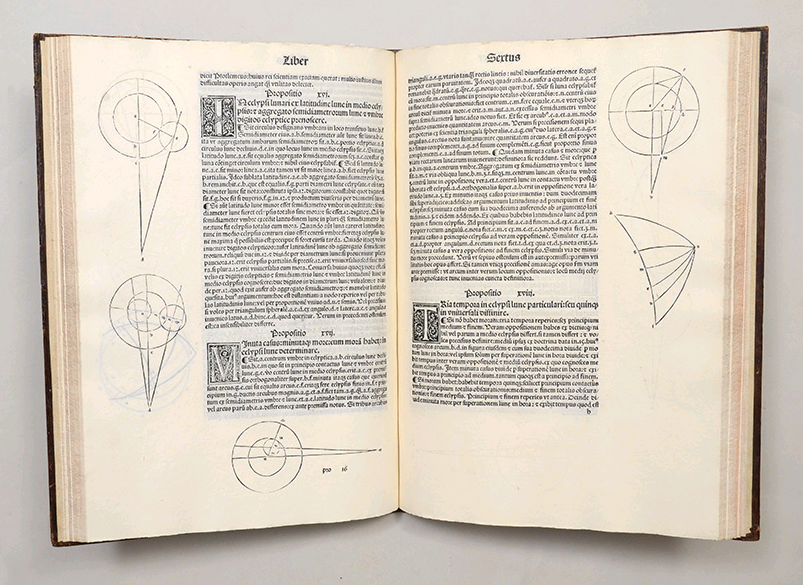

For the science collector, the most notable books in this category include the first edition of Euclid’s Elementa Geometriae (Venice, 1482), the oldest mathematical textbook in the world still in common use. Ratdolt’s printing, with its marginal geometric diagrams, remains one of the most impressive technical achievements of early printing. The master of every branch of ancient knowledge was Aristotle. His Opera Omnia, in Greek, was published in Venice by Aldus, 1495–8. From their reporting of the Socratic Method, the works of Plato stand at the origin of the Western tradition of scientific enquiry. They were first printed in Latin at Florence, 1484 or 1485, and in the original Greek at Venice by Aldus, 1513. The first publication of the works of Archimedes, the greatest mathematician and engineer of antiquity, took place relatively late (Basle, 1544).

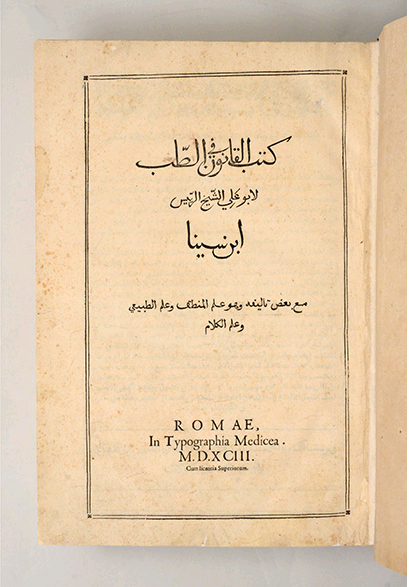

Medicine was served by the first appearances in print of the works of the Greek physicians Hippocrates (Rome, 1525) and Galen (Venice, 1490) and the medieval Arab doctors Ibn Sina (Avicenna) and Ibn Rushd (Averroes). Avicenna’s Canon Medicinae, translated into Latin, was printed at Strasbourg before 1473, and the best early collection of Averroes’ works, again in Latin, was published in Venice by the Giuntas in 1552. Another of the most important medical writers in the medieval Islamic world was the Persian physician al-Razi (Rhazes). His Liber Almansoris, a popular textbook, was first published in Milan, 1481. Yet another was Abu al-Qasim (Abulcasis); the pharmaceutical portion of his al-Tasrif was printed in 1471, the surgical portion in 1497, and his general theory of medicine in 1519.

Natural history is founded on the Historia Naturalis of Pliny the Elder (Venice, 1469), though his method of compilation strikes us not as pure science but as bearing comparison with the great medieval encyclopaedias, like the Etymologiae of the medieval Spanish bishop Isidore of Seville (Augsburg, 1472). Pliny’s most notable medieval follower was the German Dominican Albertus Magnus. His De Mineralibus (Padua, 1476) and De Animalibus (Rome, 1478) are key early printed works.

The general conception of the universe at this time was almost entirely founded on the works of the second-century Alexandrian astronomer and cosmographer Ptolemy. His Cosmographia described the earth as a perfect sphere with other planets in orderly orbits and systems around it. The first edition was published in Vicenza in 1475 without maps. When republished in Bologna in 1477 with maps, it formed the first attempt at a printed atlas.

Ptolemy’s other great work was the Almagest, a digest of astronomical knowledge. The translation of it into Latin begun by Puerbach and completed by Regiomontanus (Venice, 1496) points the way forward to the second phase of the scientific revolution: the shift from recovery of ancient knowledge to innovation.

Recent Comments